Mt. Inwang with its beautiful scenery is a Seochon landmark and featured in many traditional landscape paintings. During the Joseon Dynasty, the mountain was where scholars recited poetry and enjoyed other artistic pursuits. Today, people take to its trails for hikes and leisurely walks.

View over central Seoul from Mt. Inwang. To defend the capital city, then called Hanyang, Yi Seong-gye, founder of the Joseon Dynasty, had fortress walls built connecting the ridges of four surrounding mountains: Bugaksan, Naksan, Namsan, and Inwangsan. Standing between five to eight meters high on average, the city wall stretches 18.6 km.

ⓒ Korea Tourism Organization

Over time, the grain store became an arcade, while the hardware store became a restaurant. What were once the houses of my neighbors are now shrouded with dust barriers. Before long, they will be turned into commercial spaces. When I head out, the neighborhood landscape, which I once knew so well, feels unfamiliar to me. However, as I return home in the evening, the silhouettes of Mt. Inwang and Mt. Bugak come into view beyond Gwanghwamun Square, and I feel a sense of relief. If you stand at the intersection near the Gyeongbok Palace subway station and look up the road stretching north, the distant peaks of the two mountains appear, like a bird with its wings spread wide. Seochon may change with the times but the mountains are eternal.

Amid all the changes, Seochon remains a place of winding rather than straight paths. The alleys filled with hanok, traditional tiled-roof houses, resemble the Korean consonants ㄱㄴㄷㄹ, or sometimes form the letters ㅁ and ㅂ. As I stroll through these alleys, I am charmed by the artistic characters on the nameplates of houses and the patterns of doorknobs or iron window lattices, almost getting lost in the process. The sturdy presence of Mt. Inwang in the background thankfully guides me in the right direction.

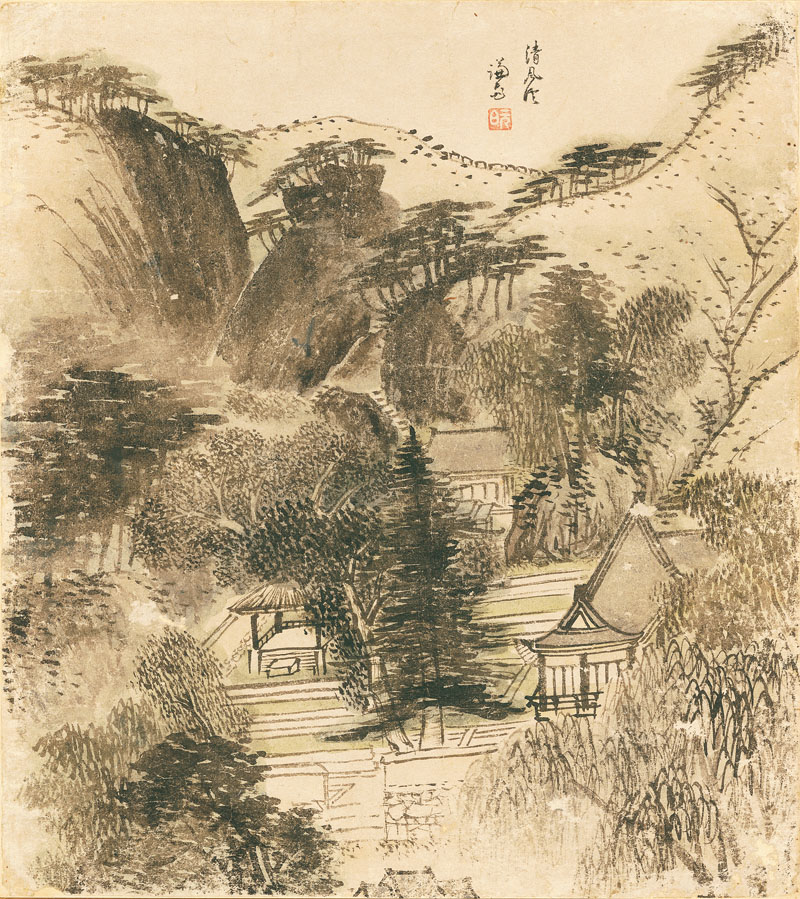

Album of Eight Scenic Sites of Jang-dong in Seoul. Jeong Seon. 1750s. Color on paper. 33.4 × 29.7 cm.

Joseon-era painter Jeong Seon, who lived in Seochon, captured on canvas eight scenic sites from his neighborhood. The painting depicts the valley at the foot of Mt. Inwang, exhibiting the masterful brushstrokes of an artist in his seventies.

ⓒ National Museum of Korea

Seochon has been at the heart of Seoul and its history since Hanyang, the city’s former name, was chosen as the capital in the early years of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). The neighborhood is home to four public libraries and twenty small bookstores, one of which is run by Han Kang, this year’s Nobel laureate in literature. I feel tempted to change the Chinese characters of Seochon’s name, so that they don’t mean “west village” but “book village.”

MAJESTIC MOUNTAINS

Mt. Inwang, to the west of Gyeongbok Palace, spans Seochon and the neighboring areas. Standing 338.2 meters high, it takes less than an hour to reach the summit from any direction. The majestic granite mountain has deep valleys that were once frequented by tigers.

During the Joseon Dynasty, Uijuro, a road so named after Uiju County next to the Yalu River, connected the Korean peninsula to the Chinese mainland. It traversed the central and northern parts of the peninsula, passing through Hanyang and going up to Uiju County in today’s North Pyongan Province. Chinese envoys used this route to enter Hanyang after passing through Pyongyang and Kaesong in the north. They would rest at Hongjewon, an inn outside the city’s west gate, and tidy their appearance before entering the capital, crossing Muakjae, the pass lying in the valley between Mt. An and Mt. Inwang. This mountain pass was very harsh for travelers, and up until the 1970s, heavy snowfall would make it so perilous that it was closed to traffic.

The Ming Dynasty envoy Dong Yue (1431–1502) recorded his first impressions of Hanyang in his travelogue Chaoxianfu: “We gaze at Hanyang across the Imjin River. Mountains enclose the city wall, looking like a soaring phoenix, radiating brilliance.” The terrain remains the same. Hikers visiting Mt. Inwang today like to take photos of themselves on the rock at the summit. On sunny days, the peaks of the nearby mountains seem to surround you.

FLORAL MONTAGE

In the past, the people of Hanyang enjoyed the spring flowers at two scenic plateaus at the foot of Mt. Inwang. Yeolyang sesigi, which records seasonal customs of the Joseon era, notes that in March, visitors would flock like clouds to Pirundae for its apricot blossoms and Sesimdae for its peach blossoms.

The Silhak scholar Pak Jiwon (1737–1805), who did not usually indulge in poetry, went so far as to write two poems about Pirundae in his collection Yeonamjip. The scenery is also colorfully described in the anthology Mumyeongjajip by 18th-century official Yun Gi: “Pirundae rises with wide, flat rocks. Bright sunshine and warm spring weather fill the city.” Sesimdae, a favorite spot for the royal family, was where the king would practice archery and read poetry with his ministers.

Today, Pirundae is located inside Baehwa Girls’ High School, while Sesimdae is part of the grounds of Seoul National School for the Deaf, rendering public access difficult.

SUSEONG-DONG VALLEY

Located to the east of Mt. Inwang is Suseong-dong Valley, a place of extraordinary scenic beauty. During the Joseon period, noble families built their homes and pavilions there, and in summer scholars gathered to indulge in pungnyu, literally “flowing wind,” which refers to the appreciation of nature and enjoyment of poetry, singing, and other arts. However, in 1971, the construction of the Ogin Apartment complex spoiled the beautiful landscape for the next forty years. When the demolition of the apartments was completed in 2012, the valley finally regained its former glory. Today, the walking paths around Suseong-dong Valley are well maintained and perfect for escaping the frenetic pace of Seoul.

A poem about the valley is found in Wandang seonsaeng jeonjip, a complete edition of writings by the late Joseon scholar and calligrapher Kim Jeong-hui (1786–1856). It begins with the line, “As I enter the valley, not a few steps / The sound of thunder roars beneath my feet,” and remarks that “it feels like night even in the day.”

Suseong-dong Valley was a popular retreat for scholars during the Joseon Dynasty. The Girin Bridge, constructed with two 3.8-meter stone slabs fitted together, is historically significant as the only stone bridge inside the ancient Seoul City Wall preserved in its original form.

ⓒ Shutterstock

This past summer, the sweltering heat in Seoul lingered past Cheoseo, the day that hot temperatures are supposed to give way to cooler weather. After several days of heavy rain that followed, I found myself hiking through the valley early one morning, umbrella in hand. Still shrouded in darkness, the area was filled with the sound of rain. Standing before the stone Girin Bridge, I could hear the clear sound of water, fully appreciating Kim Jeong-hui’s poetic sentiments in the darkness. The stream rushing down from the mountain splashed over the rocks, creating a refreshing, cheerful sound.

VIEWS OVER SEOUL

Bugak Road, which snakes across the mountainside, was opened in 1968. It was built to strengthen security around the presidential residence following a raid by North Korean infiltrators. The two-lane road starts in Sajik-dong, where the Sajik Altar is located, and stretches approximately 10 kilometers east along a mountain ridge, connecting Mt. Inwang and Mt. Bugak. In 1984, the road was divided into two at Changuimun, the northwestern gate of Seoul’s old city wall, dating to the Joseon Dynasty. The two new roads became commonly known as Inwang Skyway and Bugak Skyway, respectively, with the latter known for its romantic pavilion at the top.

A walk along the two skyways in the direction of Changuimun brings me to Mumudae, an observatory on Mt. Inwang. On clear days, it offers an unobstructed panoramic view of Cheong Wa Dae, Gyeongbok Palace, and other Seoul landmarks like N Seoul Tower on Mt. Nam and Lotte World Tower in the Gangnam area. You can faintly hear the barking dogs in Seochon and see the local bus on its village route and bicycles heading toward Suseong-dong Valley.

From here, the shortest route to the old city wall takes about 15 minutes on foot, via the wooden stairs opposite the bookstore Chosochaekbang. At the top of the stairs, the low fortress wall capped with roofstones appears, like the spine of Mt. Inwang. On my way to the summit, glancing at the mountains inside and outside the city wall, I feel as if I’m riding on the back of a tiger standing on its hind legs.

For many years, Mt. Inwang was off-limits to the public because around thirty military guard posts were installed there. With full public access granted in 2018, most of these posts were demolished, while some were turned into public rest areas. The photo shows Shelter in the Woods, a former sentry’s quarters repurposed into a cultural space.

ⓒ Studio Kenn

As I climb Mt. Inwang in the rain, the mist is thick enough to render everything in a state of emptiness. When the rain eases, I get occasional glimpses of the surrounding mountains every time the wind shifts. I can’t help but wonder if this is how the capital looked to King Taejo, the founder of the Joseon Dynasty, when he climbed up the mountain, his decision on where to locate his new capital still pending.