Natural sea salt made from seawater, sunshine, the winds of the tidal flats, and long hours of human labor is a popular specialty product of Sinan County. Indeed, about 70 percent of the country’s sea salt comes from this region. The salterns of Sinan are blessed with ideal natural conditions. Here the lives of the island people are an integral element of the distinctive landscape, whence comes this most essential ingredient in the Korean culinary tradition.

I recently spent a night on Dochodo, one of the islands of Sinan County in South Jeolla Province. It was a night of spring rain. All through the night, the rain fell on our lodgings right in front of the ferry landing. As the motel sat right by the sea, I had feared the night would be long and sleep slow in coming. Contrary to my concerns there were no sounds of the wind or the waves and my sleep was deep and sweet.

A salt worker brings up seawater by working the water mill, called mujawi. These days, this work is mostly done using motorized pumps.

Spring Awakens the Salterns

When the seawater has been dried up, going through as many as 20 steps in the evaporation ponds, the salt workers gather the salt in the crystallization pond with wooden rakes.

The vast salterns of Sinan are spread across wide swaths of several islands, including Sinuido, Jeungdo, Bigeumdo, and Dochodo. When work ceases in October, they go into their winter sleep, not to be awakened until the following March or early April. Over the winter, the weary salt fields give themselves over to the tidal flats and rest. During that time, the salt workers tend to their equipment, corroded by the salty seawater, mend the dikes, and clean up the salt pools.

The salt production period is from April to October, of which the busiest months are May to September. In Sinan, work begins at all salterns on March 28 to mark the date in 2008 when the official classification of sun-dried sea salt was, as the locals like to say, “upgraded to food from minerals.”

The west coast tidal flats of Korea are among the five most important tidal flat areas in the world, and some 44 percent of Korea’s tidal flats are found in Sinan County. The salt produced in Sinan has a particularly high mineral content and exceptional taste thanks to the region’s topography that s a thickof sediment, which infuses the salt with additional organic matter. Spread out like blood vessels across the thick tidal flat s sitting atop the islands’ bedrock are networks of streams called tidal waterways. These waterways, which add the exquisite finishing touch to the tidal flat landscape, serve as a respiratory system that enables the flats to breathe and purify themselves.

Start of the Sinan Salterns

In Korea, salt was traditionally made by boiling down seawater. The solar evaporation method of harvesting sea salt through exposure to the sun and the wind was introduced by the Japanese during the colonial period (1910–1945), with a trial operation in Juan, Incheon. Salterns were first built in Sinan in 1946, right after Korea’s liberation from Japanese rule. Park Sang-man, a native of Bigeumdo who had been coned into the Japanese army, was forced to work on salt fields in South Pyongan Province, in what is now North Korea. When he returned to his island home after liberation, he used his knowledge from that experience tosalt farms in cooperation with local residents. Gurim Salt Farm is recognized as the first saltworks in the Honam [Jeolla] region. In 1948, a cooperative was formed by 450 households of Bigeumdo, who joined hands to establish the 100-hectare Daedong Salt Farm. According to records of Sinan County, Bigeumdo today is home to 226 salterns that generate annual revenues of more than 10 billion won (about $8.5 million).

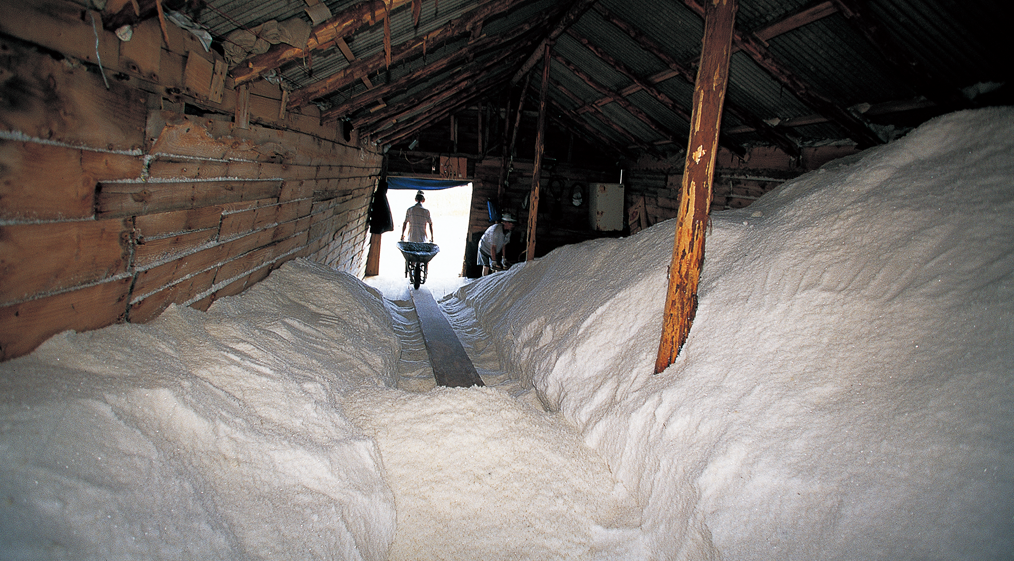

A wheelbarrow chock-full of salt is taken to the salt storage shed. The storage shed is designed to allow the bittern to drain out by making a water channel under the wooden planks of the floor.

A wheelbarrow chock-full of salt is taken to the salt storage shed. The storage shed is designed to allow the bittern to drain out by making a water channel under the wooden planks of the floor.

“Many people on Dochodo are mainly farmers but also make salt on the side. In the salt making season,we get up at two or three in the morning and work in the salt fields till seven or eight.That leaves time to do something else during the day.”Park Seong-chang

Seongchang Salt Farm, DochodoPark Seong-chang runs a saltworks that bears his name: Seongchang Salt Farm. He started making salt much later than most around him. After spending most of his working life as a primary school teacher, in 2007 he returned to Dochodo, his island hometown, and took over his father’s saltern operations. Having made a late start, he worked with extraordinary passion and tenacity to produce the highest quality salt that would earn brand loyalty among customers.

The starting point is everything. The reservoir holding the seawater that is his raw material sat on high ground, making it difficult to draw seawater. There were many seasons when he could not make any salt. So over five winters, he hired workers and backhoe equipment tonew water channels through which seawater could flow into the reservoir twice a day. As a result, unlike other salterns which store a lot of seawater for use over a long period, Park’s salt fields constantly receive fresh inflows.

In the winter, when salt making is suspended, there are many important chores to be done. The soil in the ponds where the salt is produced during the season must be turned over to a depth of 10 centimeters to remove the salt crust on the bottom and expose the soil to greater air circulation. If the salt yield is unsatisfactory, then once every several years the soil is turned over to a greater depth with a backhoe. Salt farmers have different ideas about when this should be done. Some do it in November, after the year’s salt has been harvested, but Park opts for late January or early February because he believes this helps to minimize the salt crust that can form if it happens to rain before the salt crystals are properly formed.To one side of the saltern, which covers an area of four hectares, is a 330-square-meter drying shed where salt bales weighing 1,200 kilograms are suspended in rows. Park devised this method for removing the bittern from the salt instead of following the regular practice of sitting the bales on pallets with drainage holes on the bottom. When stored in these bales made of a special material, the bittern can be removed within five days. When all the moisture is removed, the bales weigh about 650–750 kg. The flavor of the salt is determined not by the harvesting process but its storage and maturing period, Park says.

Seongchang Salt Farm has received ISO 22000 certification for food safety from the Korea Certification Association. Park has also received the New Intellect Award, bestowed by the government to innovators who “ added value using their knowledge and new ways of working by thinking outside the box.” Pride in being the first salt farmer to earn this award drives Park to work even harder.

“At first I worked at the National Agricultural Cooperative [Nonghyup]. But since I lived close to the salterns, I thought it would be better to work close to home rather than commuting far away. I didn’t mean to do it for very long, but somehow more than 40 years have passed.”Lee Mun-seok

Taepyung Salt Farm, Jeungdo“I go to work at about seven and come home when the sun sets,” says Lee Mun-seok. Though past the age of 80, Lee still walks with a straight back and his eyes are bright and clear. He still goes to work every morning and spends the day looking after the company’s halophyte garden or tending to other tasks in the salt fields.

Or, he would scrape out the insides of soy beans or red beans, fill them with pine resin, and float them in the brine to see how much they would sink. Brine salinity is now measured by an instrument called ppomae. The dayswhen water mills called mujawi were used to draw in seawater are also long gone, as that work is now done by motorized water pumps. The wheelbarrows that transported the salt have largely been replaced by carts on rails, and the straw bales for carrying the salt have also vanished. Instead of using a hand shovel to load salt onto a lift, the salt is loaded onto a conveyor belt that automatically dispenses it into carts.

Though he has lived through those difficult times, Lee says he has no particular advice for younger salt workers. He simply says, in a matter-of-fact way: “Those are the kinds of things you teach or learn on the job.”

He adds that he knows when rain is coming, even if the weather bureau doesn’t. A faint but definite smile of pride appears on his faceand quickly disappears. If the wind coming over the sea carries the briny smell of the flats, then that means rain, he says. And how can such things be conveyed in words or writing? Lee says he wants to live out the rest of his life like salt. Though salt can extract the moisture from things, it does not change or take away their essence.

The salt farmer’s day starts at three or four in the morning. As the salt making season lasts five months of the year at most, every minute has to be used to full advantage.

“I believe the continued prosperity of the salterns is linked to preventing the stories of the islands from disappearing even when the elderly villagers who have safeguarded them all this time are gone. In this way, we can revive and hand down the time-honored culture of the villages.”

In 1953, after the armistice halted the Korean War, a largescaleland reclamation project began on the island of Jeungdo.The waterway that separated one side of Jeungdo from the otherwas filled in as part of a project to assist war refugees. Despite alack of proper tools, an embankment was built between the twoparts of the island and salt fields were d. This was the startof Taepyung Salt Farm, now the biggest in the country with an areaof over 300 hectares. With an annual production volume of some16,000 tons, it accounts for 6 percent of all salt made in Korea.

A saltern is where seawater is evaporated by the sun and thewind to produce salt. In the first stage, seawater is stored in reservoirsso the impurities can sink to the bottom. The brine thengoes through anywhere from 10 to 20 steps in evaporation ponds toincrease the level of salinity. In the reservoir, the brine has a salinityof 3 percent, but by the time it reaches the crystallization ponds,where the salt is formed, the level of salinity reaches 25 percent.From the first evaporation pond to the crystallization pond, it takesroughly 20 days for seawater to become salt.

A thin crust begins to form in the crystallization pond. The “salt flowers,” or the so-called seeds of salt, bloom and grow, and then gradually sink to the bottom to turn into full crystals.

From Seawater to Salt

In the crystallization pond, a thin crust begins to form. This means the “salt flowers,” the so-called seeds of salt, have started to bloom. These salt flowers, which are fine crystals, gradually grow larger and then sink to the bottom. Under the intense heat of the summer sun, this process can take just 30 minutes. Initially a hollow hexagonal shape, the salt grains fill out both inside and outside. While the grains grow in size, only the salt that retains the empty space within will be of the highest quality. This space, called an “air gap,” allows humidity in the air to be repeatedly breathed in and out. Without these air gaps, the salt may dissolve in water but there is no air circulation.

Humid winds increase production volume but lower the quality of the salt. And if rain should suddenly fall, the brine in the evaporation ponds must be quickly transferred into storage tanks.

Hence, the salt workers cannot leave the fields unattended even for a moment. The harvested salt is left in storage for a long time to remove the bittern. The longer this natural dehydration process, the better the flavor of the salt is said to be.

The halophyte garden of Taepyung Salt Farm on Jeungdo features sea plants such as samphire, cogongrass, and sea blite, whicha beautiful landscape.

“I seek out any place where there’s something to learn about sea salt. I’ve been to Guérande [Brittany, France] twice, as well as salterns in Sicily and Vietnam. There’s one thing I’ve learned for sure. It’s all the same sea salt, but they are more skilled at secondary processing.”Choe Hyang-sun

Namil Salt Farm, BigeumdoIn 1948, around the time Daedong Salt Farm was established, a school for sea salt specialists was set up on the site of present-day Bigeum Elementary School to train workers for salt farms on the nearby islands. One individual who provided considerable financial support for creating the saltern was the then shipowner Myeong Man-sul. Then, in the 1960s, Myeong took over the saltern.

In 1981, Choe Hyang-sun married Myeong’s second son, Myeong O-dong, and together they now operate Namil Salt Farm.

In the early days of Choe’s marriage, when they lived with her inlaws, she listened to countless stories told by her father-in-law. Though most of the elders of the family have since passed away, among those who gathered at the house were those who madesalt, those who made carts to draw up the seawater, and still others who made the straw bales to carry the salt. Among the things which Choe’s mother-in-law told her, there is one that still fuels her passion: Her father-in-law, though he owned the salt fields, believed that they did not belong to himself alone, but rather all the local workers who produced the salt. Therefore, he did not sell the saltern to any single individual but divided it into lots and turned over ownership to the island’s residents. This is why Daedong Salt Farm, established with the collective efforts of local workers, has not passed into the hands of an outsider. It remains the property of the islanders’ descendants. In 2007, it was designated a Modern Cultural Heritage in recognition of its rich cultural landscape.

Myeong Man-sul has left many marks on the family’s ancestral home in Jidang-ri, Bigeumdo. There used to be a mound of neatly squared stones, brought over from the mainland, with which he intended to build a salt roastery. But this plan was never realized and the stones were later used to build walls around the house and a shed. Choe’s mother-in-law, who had maintained the house all this while, passed away last year.

Choe came to live on the island with her husband believing that a saltern was where “you simply swept up the salt with a broom.” But their resolute determination has enabled them to put plans into action, which sometimes seemed “crazy.” Indeed, they produced ten thousand 20 kg sacks of salt last year. The salterns require continuous investment. Accepting her fate, Choe now goes anywhere inside or outside Korea where she can learn about sea salt. When it comes to her study of salt and exploring the industry’s future direction, she is perhaps even more passionate than her husband. The island’s first female village head, Choe is now heading a committee toa solar salt zone comprising the five villages of Jidang-ri.

Passing Down the Culture of Salt Fields

With the opening of the domestic salt market under the Uruguay Round agreement of 1997, there was much uncertainty about the future competitiveness of Sinan’s sea salt industry. In fact, many salterns did indeed close down. But the inherent value of natural sea salt, an essential ingredient in the fermented foods that are at the core of the Korean culinary culture, proved strong enough to overcome the challenge. What is often overlooked in a technical comparison of the ingredients of rock salt, refined salt, and sea salt is the natural microbes contained in sea salt. These microbes play an important role in fermentation of foods and have long helped Koreans to stay healthy. The five tastes present in the sea salt from Korean shores is also a selling point that is not easily accepted by consumers in other countries, who have their own flavor preferences.

These days, Taepyung Salt Farm is a leading tourist attraction of Jeungdo, a recently recognized “slow city.” Visitors to the salt fields can tour the Salt Museum and gain firsthand experience in salt making in the activity area. The halophyte garden displays a variety of sea plants, such as samphire, cogongrass, and sea blite. The salt cave healing center is a cozy place to relax.

“We now combine the primary industry of salt production, the secondary industry of salt processing, and the tertiary industry of tourism,” explains Jo Jae-u, director of Taepyung Salt Farm. “We take as much interest in maintaining the island community as we do in increasing the output of salt. The salt workers are steadily growing older, while the sense of community seems to be gradually weakening. I believe the continued prosperity of the salterns is linked to preventing the stories of the islands from disappearing even when the elderly villagers who have safeguarded them all this time are gone. In this way, we can revive and hand down the time-honored culture of the villages.”

In the Salt Museum’s activity area at Taepyung Salt Farm, visitors try their hand at raking up the salt.

Kim Young-ockFreelance Writer

Ahn Hong-beomPhotographer