It’s less than two decades since the turn of the century, but if we look at how far Korean cinema has cometoday, the 20th century seems like ancient history. Changes in the domestic film industry have been immensein the 21st century. And yet, Korea has still not marked out its own territory on the world’s movie map.

The red carpet event for the VIP screening of “Train to Busan,”held on July 18, 2016 at the Yeongdeungpo Time Square, in Seoul,attracts a huge crowd. This gala event for the opening of a Koreandisaster blockbuster shows a slice of Korea's film industry of the21st century.

Im Kwon-taek’s “Chunhyang”(2000) is thefirst Korean movie everselected for the maincompetition sectionof the Cannes FilmFestival.

In Korea, up until the 1980s it was not hip to gosee Korean movies. For a long time, most Koreanstended to dismiss domestic productions forbeing down-market tearjerkers. In the 1960s, Koreanmovies were diverse and distinctive in their ownway, but over the next 20 years the industry’s developmentwas hampered by restrictions and censorshipunder dictatorial regimes, as well as the fastgrowing popularity of television. Political and socialchanges thereafter sparked a renaissance in Koreancinema in the mid-1990s. New movements wereled by intelligent, and intrepid, young producersand ambitious directors with an artistic eye. Koreanmovies achieved huge advances in terms of artistryand commercial appeal.

International perceptions began to change aswell. In the mid-1990s, a Korean studying film inParis might well have been asked, “Do you makemovies in Korea?” Except for a handful of filmexperts, very few foreign film enthusiasts had evenseen a Korean production. But things changedmarkedly entering the 21st century. Korean workswere invited to prestigious international film festivalsand won major awards. And a new generationof directors who had debuted in the latter half of the1990s, such as Hong Sang-soo, Kim Ki-duk, ParkChan-wook, and Bong Joon-ho, attracted a sizeablefollowing among overseas audiences.

A scene from LeeChang-dong's “Oasis”(2002), the love story ofa woman with cerebralpalsy and a socialmisfit.

Rapid Development

Few countries have seen such rapid growth oftheir film industry as Korea. The number of movietickets sold exploded from 61.69 million in 2000 to217.3 million in 2015, while the number of domesticproductions jumped more than fourfold, from 57to 232, and the number of screens surged from 720to 2,424 during the same period. Box office revenues hit 2.11 trillion won (about $1.83 billion) in2015, compared to 1.52 trillion won in 2005. (Noaccurate box office data prior to 2005 is available.)Still, this is nothing compared to China’sfilm market. After recording an unbelievable64.3 percent growth rate in 2010, China’s filmindustry has continued to surge 30 percent peryear. And with the number of movies viewed percapita standing at a mere 0.92 in 2015, robustgrowth is forecast in the years ahead. Except forChina, however, Korea has experienced morerapid expansion of its film industry than almostany other country.

The most remarkable growth is found in thenumber of movies viewed per capita. In 2000,each Korean saw an average of 1.3 movies. Thisfigure more than doubled to 2.95 in 2005, andthen reached 4.17 in 2013, and 4.22 in 2015.These numbers are especially noteworthy comparedto the corresponding figures for 2013: 4.0in the United States, 3.14 in France, 2.61 in theUK, 1.59 in Germany, and 1.22 in Japan. Evenin India, which produces more movies than anyother country in the world (1,602 titles in 2013),the per capita figure stood at 1.55.

Choi Min-sik acts asthe genius artist JangSeung-eop of the late19th-century JoseonDynasty in “PaintedFire” (2002), directorIm Kwon-taek’s 98thfeature film.

So, what is the driving force behind theseamazing numbers? One possible answer is thegovernment’s film promotion policies. Under astrict screen quota system, each movie screenmust show local movies for at least 73 days ayear. Directors also receive support from varioussources, including the Korean Film Council, regional film committees, local governments,and international film festivals. Once again,aside from China, which imposes strict restrictionson the import of foreign movies, Koreaprovides the highest level of support for promotionof domestic films.

Thanks to a variety of support measures, thebox office has come to be dominated by Koreanproductions. In 2013, domestic titles held amarket share of 59.7 percent and have sincecontinued to account for around half the market,standing at 50.1 percent in 2014 and 52.0percent in 2015. Aside from the United Statesand India, where domestic films captured marketshares of 94.6 percent and 94.0 percentrespectively in 2013, Korea is a rare countrywhere local titles are more popular than Americanmovies, along with China (58.6 percent) andJapan (60.6 percent). Corresponding figureswere 33.8 percent in France and 22.1 percentin the UK (including co-productions with othercountries).

Other factors contributing to expansion ofthe Korean film market include the lifting ofcensorship and the emergence of a growingnumber of talented young directors. Of course,the market has now clearly entered a newphase. As thresholds are reached in the numberof movies viewed per capita and the numberof available screens, and as film promotionpolicies run their course, growth patterns arebound to change in the future.

A scene from “The Face Reader” (2013), directedby Han Jae-rim. Kim Hye-soo acts as Yeonhong, aseductive entertainer and face reader.

An iconic scene from “The Thieves” (2012), directedby Choi Dong-hoon, a comic action thriller featuring10 thieves chasing one diamond.

State of Korean Cinema

In 2000 Im Kwon-taek’s “Chunhyang” became the first Korean film selected forthe official competition section of the Cannes Film Festival since the festival’s inaugurationin 1946, marking a breakthrough for Korean cinema. While a nominationfor Cannes’ Palme d’Or is by no means the ultimate standard, it can be said thatheretofore Korean productions simply did not exist on the world’s movie map, chartedout by Western film professionals and critics. “The Oxford History of World Cinema”(Oxford University Press), published in 1966, does not mention a single Koreanmovie; in other film-related publications Korea was invisible as well.

| 1 |

A scene from “The Chaser” (2008), directed by NaHong-jin. The thriller features a serial murderer,his victims, and a pimp and former police detectivewho chases the murderer. |

| 2 |

A scene from “Veteran” (2015), directed by RyooSeung-wan. The film depicts the underworld life ofa third-generation conglomerate heir. |

| 3 |

A scene from “The Handmaiden” (2016), the latestmuch talked-about film by Park Chan-wook. |

| 4 |

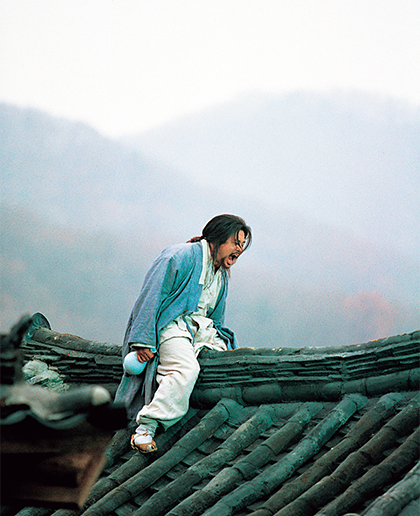

A Scene from “Jeon Woochi: The Taoist Wizard”(2009), directed by Choi Dong-hoon, a comic heromovie set in the Joseon period. |

But things started to change at the turn of the century. In 2002, Im Kwon-taekwon the Best Director Award at Cannes for “Painted Fire.” In 2004, Park Chan-wookwon the Grand Prix for “Oldboy” and in 2009 the Jury Prize for “Thirst.” Meanwhile,in 2007 Jeon Do-yeon won the Best Actress Award for her role in Lee Chang-dong’s“Secret Sunshine”; the director himself won the Best Screenplay Award in 2010 for“Poetry.” Three of Hong Sang-soo’s works and two of Lim Sang-soo’s works wereselected for the main competition at Cannes, though they failed to receive any prize.

Actor Song Kang-hoand actress Kim Ok-binin a scene from “Thirst”(2009), a thriller featuringa priest turnedvampire, directed byPark Chan-wook.

At the 2002 Venice Film Festival, Lee Chang-dong’s “Oasis” won the SpecialDirector’s Award and lead actress Moon So-ri won the New Actress Award. Kim Kidukearned the Best Director Award for “Samaritan Girl” in 2004 at the Berlin FilmFestival, and for “3-Iron” at the Venice Film Festival the same year. He also capturedthe Golden Lion for best movie at the 2012 Venice Film Festival for “Pieta.”

With these notable achievements over the past 10 years or so, Korean cinemahas been earning high acclaim from international audiences in the 21st century. Andyet, we can’t really say Korea has carved outa prominent position for itself on the world’smovie scene. Every 10 years the British filmmagazine Sight & Sound releases a list of “TheGreatest Films of All Time,” based on a surveyof film critics and directors from around theworld. For the 2012 list, no Korean film made itinto the top 100. Of course, this was not unexpected.But of the six Asian films that havemade the annual top ten lists since 2000, noneare Korean.

There’s no real need to take these lists tooseriously. They will continue to change in thefuture, and many movies, as always, will cometo receive greater acclaim in the days ahead,rather than at the present. But Korea’s absencefrom these lists seems to indicate that manyfilm experts do not regard Korean works to beat the vanguard of film aesthetics.

Here, we need to reflect on the designation“Korean movie.” It contains a subtle dualism, asdo the tags “Indian movie” or “British movie.”That is, it’s not clear whether these labels simplydenote country of origin or express somegreater common point of reference. Attemptsto generalize the character of movies originatingfrom a particular region canpreconceptionsthat lead people to overlook theunique strengths of individual films. Nevertheless,an indefinable regional color is ingrained,sometimes indelibly, in movies sharing a commonorigin. Then, what is it that makes Koreanmovies Korean? In other words, what regionalcharacter can be found in the creations of filmmakerssuch as Hong Sang-soo, Bong Joon-ho,and Lee Chang-dong, as well as those of ParkChan-wook and Kim Ki-duk?

Attempts to generalize the character of movies originating from a particular region canpreconceptions that lead people to overlook the unique strengths of individual films. Nevertheless, anindefinable regional color is ingrained, sometimes indelibly, in movies sharing a common origin. Then,what is it that makes Korean movies Korean?

There is no simple answer to this questionbecause their movies actually have very littlein common. The works of Hong Sang-soo andKim Ki-duk may belong to a branch of Europeanmodernism, while those of Park Chanwookand Bong Joon-ho (and occasionally KimKi-duk) can be seen as aesthetic variations of“Asian extreme.” In other words, Korean cinemais a conglomeration of diverse film typesthat cannot be defined by any single regionalcharacter, an aspect that makes Korea’s locationon the world’s movie map unclear.

| 1 |

Hwang Jung-min actsas a shaman in “TheWailing” (2016), directedby Na Hong-jin, setin a rural village wherea series of mysteriouskillings take place. |

| 2 |

A scene from “The HighRollers” (2006), directedby Choi Dong-hoon,featuring a band ofunderground gamblers. |

| 3 |

A scene from “Kingand the Clown” (2005),directed by Lee Joonik,which claimed to bethe “first royal courtburlesque” in Koreanfilm history. |

Directors with Diverse Leanings

Korean cinema today is so diverse that it cannot be summed up in a few generalcharacteristics. For the sake of discussion, they can be divided into four broad categories.

The first category can be called “national realism.” Without question, the leaderhere is Im Kwon-taek. This giant, who has long been the poster boy of Koreancinema, concentrated on mainstream fare in his youth, but from the mid-1970she struggled to bring a new aesthetic to “national cinema.” He released his 102ndmovie, “Revivre,” in 2012. Another legitimate member of this group is Lee Changdong,a moralist who stands on the opposite side of inveterate pleasure-seeking infilm. He has been inactive since his release of “Poetry” in 2010. Im Sang-soo, whodirected “The Housemaid” (2010) and “The Taste of Money” (2012), also belongshere, though he is much more of a free spirit. These directors have focused onKorea’s regional characteristics in their depictions of historical incidents and reallifeabsurdities. Also tying them together is the priority placed on theme over styleand form. An upcoming younger-generation director who is willing to take on thistype of national cinema has yet to appear.

Jun Ji-hyun plays alead role in “Assassination”(2015), directedby Choi Dong-hoon.Critics praised it as thefirst Korean movie tofeature a woman at thecenter of the resistancemovement againstJapanese colonial rule.

The second category is “modernism.” Hong Sang-soo and Kim Ki-duk can be placed in this category but their differences aregreater than their similarities. Through innovationof form, Hong Sang-soo seeks toa new sense of reality, whereas Kim Ki-duk isengrossed with the notion of salvation throughphysical suffering. A handful of younger directorsare making films that could be seen in thislight, but none of them is widely known yet.

The third category is “genre innovation.”Directors who belong here are those whohave earned a measure of popular and criticalacclaim, including Park Chan-wook, BongJoon-ho, Kim Jee-woon, and Ryoo seung-wan.With a fanboy background, they are all captivatedby B-grade movies, or genre movies. Theirown mixed-genre creations are based on thrillersor action movies with a smattering of comedyand horror and other elements thrown in.Though mass-audience-friendly, these films attimes also reveal aspects of the stubborn stylist.In this category as well, the directors shownoticeable differences from one another. ParkChan-wook reinterprets classical tragediesas genre movies while Bong Joon-ho fusesregional politics with genre film dynamics. RyooSeung-wan and Kim Jee-woon never abandonfanboy tendencies even when tackling relevantissues. Of these genre innovation films, BongJoon-ho’s “The Host” (2006) and Ryoo Seungwan’s“The Berlin File” (2015) attracted over 10million viewers each and have come to serveas a model for many of their fellow filmmakers.Among them is Na Hong-jin who has come tonotice for “The Chaser” (2008), “The Yellow Sea”(2010), and most recently “The Wailing” (2016).

The fourth category is mainstream movies,under which the greatest number of directorsfall. For some time, the leader was KangWoo-suk, but from the mid-2000s he has beenreplaced by such figures as Choi Dong-hoon andYoun Je-kyun. Indeed, Choi Dong-hoon alreadyhas two 10-million-viewer mega-hits under hisbelt, and all five of his films, from his 2004 debutwork “The Big Swindle” to “Assassination” in2015, have enjoyed commercial success.

It is hard to say that any one category speaksfor Korean cinema better than the others. Thevery diversity generated by these directors isshaping the dizzying yet dynamic face of Koreancinema.