Jung Young-sun, a trailblazing Korean landscape architect, has transplanted the Western concepts of this practice to suit Korea’s land, climate, and way of life. Her work is evocative of landscape paintings: nature and humans, time and place coexist with mutual respect. This reflects her belief that landscape architecture is, at its core, the practice of creating spaces for everyday life.

Won Dharma Center was built in New York to facilitate Won-Buddhism’s outreach efforts in the United States. The design respects the existing order of the vast land, merging architecture and landscape into a single organic entity and embodying the value of mutual coexistence.

Courtesy of Won Dharma Center

In Poetry on Land (2024), a documentary film about Jung Young-sun’s life and work, “the land” is the most frequently spoken phrase apart from “landscape architecture.” Jung does not see land as a geopolitical or economic concept, but as a living landscape layered with time, memory, life, and sensation. Her work begins by reading the context of a space, and evolves into an attempt to recover the uniqueness and relationships between the places that make up the land on which she creates.

Born in 1941, Jung Young-sun is a pioneering Korean landscape architect. Throughout her over fifty-year-long career, she has paid heed to the voices of the land and worked hard to conserve local biodiversity.

Courtesy of Harper’s BAZAAR Korea; Photo by Pyo Ki Sik

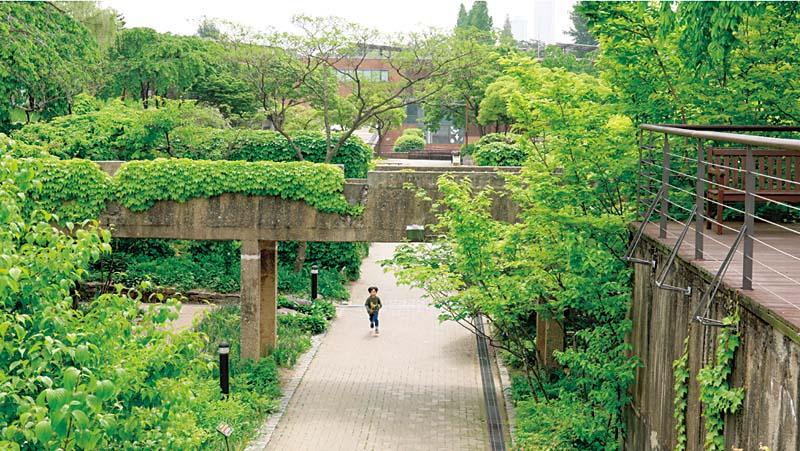

A scene from director Jung Dawoon’s documentary Poetry on Land. Seonyudo Park, created from a former filtration plant, offers diverse spaces to explore and experience.

© Giraffe Pictures

PERCEPTION OF THE LAND

For Jung, land is not something to be filled, but to be emptied and regarded. She believes that reckless urbanization and uniform land development have erased the special landscapes that once existed. To counter this, she tries to revive the original fabric of the land in her work, approaching its history, ecology, and traces of humanity with respect.

This design philosophy is most evident at Seoul Botanic Park, located in the western part of the capital city. In this project, Jung minimized human intervention to follow the contours of the existing wetlands, waterways, and willows, respecting the natural flow of the landscape. Visitors won’t find formal planting schemes here. Instead, there is an ecological rhythm — harmony between water and vegetation, offering a sensory experience of the land’s original character.

Seoul Botanic Garden was created as a haven for various plant species, giving visitors an escape from the ordinary urban landscape.

Jung’s perception of the land is also deeply embedded in Yeouido Saetgang Ecological Park. Yeouido, the political and economic center of Seoul, is known for its skyline shaped by towering high-rises. A river, the Saetgang, flows quietly along the edges of this former island, providing a contrast to its urban landscape. The abandoned waterway, once confined by concrete embankments and nearly lifeless in ecological terms, was transformed by Jung into a living green space. She sought to restore the relationship between the city and its ecological community by reviving the site’s original natural character. All artificial fixtures were removed, the water was purified, and the banks were carefully reconstructed to allow the river and wetlands to function independently once more.

The issue of public accessibility was equally important. Jung created spaces where people could walk along the embankments and old railroad tracks, which they had once hurried past without noticing. She also reopened connecting roads so that people could regain a sensory awareness of wild plants and birds living and breathing around them. The project reveals how nature and forgotten qualities of the land can be revived.

Jung also recognizes the land as a site of sensation and experience. She believes that one must be able to walk on, touch, smell, and hear the land — to feel it with all the senses. Landscape architecture is about connecting all these senses, with the land at center stage. Restoring these sensations plays an important role in the rooftop garden Jung designed at the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju. In this unusual setting, she wanted to interweave the land and sky, wind and plants, and people’s movements into a lively landscape. As visitors walk the vast “land” spread across the rooftop, they feel Gwangju’s history and breathe in its nature. The project went beyond laying soil and planting native trees, creating a vertical extension of the Korean landscape.

At the end of the day, the land that Jung refers to is not Korea’s national territory but rather a self-portrait of the lives, time, and memories that have accumulated in its space. Jung understands the landscape architect’s role as not simply building something on the ground but reviving things, allowing them to be seen again. She says the land is like a poem that needs to be reread, with landscape architecture another language in which that poem can be recited.

Yeouido Saetgang Ecological Park allows guests to enjoy forests and wetlands in the heart of Seoul. created with input from specialists in birds, insects, fish, and plants, the park is an ecological treasure along the Han River.

© Seoul Tourism Organization

PUBLIC AND POLITICAL DIMENSIONS

Jung believes that creating public spaces available to everyone is the beginning and end of landscape architecture. The goal is not a magnificent or monumental space but one where everyone can walk, rest, and stay a while. She also focuses on the political dimension, seeing landscape architecture as a mechanism that reveals and reconciles social structures and the flow of power, as well as the imbalances of everyday life. She puts the user’s perspective first, always asking herself of each individual bench, tree, or path, “What is this for? How will it be used?” This approach is even more pronounced in her public projects. Rather than catering to the aesthetics of a certain class, Jung designs spaces that are equally accessible to and usable by everyone.

What distinguishes landscape architecture, in Jung’s view, is its inherent public nature. Her design process begins with deep consideration of the users, imagining a place where anyone can sit, pass through, or linger. In Jung’s definition, landscape architecture is both inclusive and impartial, “a space that embodies the democracy of everyday life.” She has manifested this philosophy in many of her public projects for the city of Seoul. Her efforts go far beyond the creation of beautiful scenery; she thinks carefully about how landscape architecture can dissipate the concentration of power and gaze in the city, connect people, and enable social dialogue. In this way landscape design becomes an instrument for social coordination.

The serenity and deep resonance of Jung’s work comes from the way it expresses her attitude and philosophy, reaching beyond technique into something more reflective. In her hands, landscape architecture creates spaces of quiet openness, where life has room to breathe.

A model for the design of Seoul Arts Center. In the 1980s, economic growth and resulting changes in lifestyle drove planning for diverse cultural institutions and leisure facilities. This arts complex in southern Seoul is a prime example of how landscape architecture can meaningfully shape leisure spaces.

Courtesy of National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

THE KOREAN WAY

Jung’s work is underpinned by two profound questions: What is landscape architecture? And how should it exist in Korea? She has sought the answers both in her work and her attitude towards nature and people, with a philosophy that earned her international recognition when she received the IFLA Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe Award in 2023. According to the International Federation of Landscape Architects, “Jung’s approach…‘translated’ the unfamiliar concept of landscape which originated from the West to fit Korean land and landscape.” This suggests that the sensibility she demonstrates goes beyond merely adding local color. Indeed, her aesthetic is a refined approach that renews the global language of landscape architecture by delicately tracing the essence and relationships of a place.

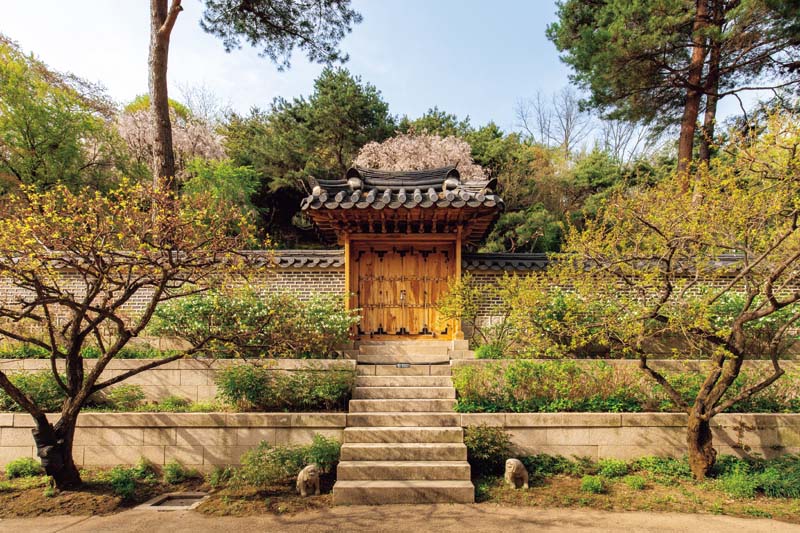

Traditional garden Hee Won at the Hoam Museum of Art, run by the Samsung Foundation, marked a turning point in Jung’s embrace of traditional elements. It reflects the aesthetics and architectural features of a traditional Korean garden, including flower terraces, ponds, stone walls, and pavilions.

© Hoam Museum of Art

Jung stresses that Korean landscape architecture must harmonize with its surrounding scenery. Elements like buildings, trees, waterways, and paths gain meaning only within the relationships and flows of a visual perspective — foreground, middleground, and background. In this context, Jung values the concept of chagyeong, or “borrowed scenery.” This traditional technique incorporates external natural views into a garden. Jeong sees it as both a visual method and an attitude toward the world that invokes a humble, reverent view of nature.

The result is that Jung’s work does not reproduce tradition nor attempt to restore traditional forms or symbols. Instead, she reinterprets traditional Korean views of nature, perceptions of landscape, and attitudes toward life in contemporary language. The Geoffrey Jellicoe Award, beyond recognizing her individual achievements, signified how the Western-centric concept of landscape architecture could evolve in a different direction through Korean landscapes and philosophy. Describing her design process as “orchestrating so that nature can speak,” Jung makes sure that while her work remains understated, nature always comes to the fore.

In essence, Jung’s work is not about designing land, but about creating scenes that allow people to reconnect with nature. Quietly, she takes the subtle beauty of a landscape beyond the wall and weaves it back into our everyday lives.

Osulloc Tea Museum on Jeju Island was opened by beauty brand Amorepacific to promote Korea’s tea culture. Jung created a garden that embraces the building and blends Jeju’s tea fields with the surrounding natural landscape.

© Kim Yong-kwan