Countless cities across the globe are home to historical and cultural heritage sites spanning thousands of years. But there’s something special about Gyeongju. Staying at a guesthouse built in the style of a traditional Korean house where massive ancient tombs come into view when you open the door, you’re transported back in time to the ancient Silla Kingdom.

The Daereungwon Ancient Tomb Complex consists of 23 tumuli belonging to kings, queens, and aristocrats from the Silla Kingdom. Excavations have been conducted since the 1920s, yielding numerous artifacts, from gold crowns and ornaments to everyday items.

© Korea Tourism Organization

Gyeongju, a city in southeastern Korea, was the capital of the Silla Kingdom (57 BCE–935 CE). For a thousand years it functioned as the political and cultural center of ancient Korea, from the Three Kingdoms period (1st century BCE–7th century CE) to the Unified Silla period (676–935).

The Gyeongju Historic Areas were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000. Encompassing 52 designated cultural properties spread across five areas — the Wolseong Belt, the Tumuli Park Belt, the Namsan Belt, the Hwangnyongsa Belt, and the Sanseong Belt — they offer comprehensive insight into Silla’s history and culture. A majority of the sites have been remarkably well preserved, heightening their historical value. There are only a few other cities around the world, such as Istanbul or Vienna, where the entire historic center has been designated as a World Heritage Site.

Donggung and Wolji, a palace and pond, respectively, comprise a historic site that sheds light on landscaping design of the Silla period. Donggung was the residence of princes and a venue for state banquets.

© gettyimagesKOREA

MILLENIAL PALACE SITE

The Wolseong Belt and the Tumuli Park Belt offer a window into the royal culture of Silla, a kingdom that lasted a thousand years. At the center of the former is the Wolseong Palace Site, the ruins of Silla’s fortified royal palace compound. The half-moon shaped fortification measures 890 meters from east to west, and 260 meters from north to south, with a circumference of around 2,340 meters. During the reign of King Munmu (r. 661–681), the compound was expanded to include Donggung and Wolji — a palace and pond commonly known together as Anapji — and Cheomseongdae, recognized as the oldest extant astronomical observatory in Asia. Also nearby is Gyerim, a forest that is the legendary birthplace of the progenitor of the Gyeongju Kim clan. Of immense historical value, the palace site is a window into Silla’s development, prosperity, and collapse.

Donggung and Wolji constitute Silla’s secondary palace site. Donggung, the Eastern Palace, was the residence of princes as well as a venue for banquets held during state events or to host honored guests. The reconstruction of the present lake and several palace buildings, based on historical records and research, was completed in 1980. The addition of lighting in the buildings creates beautiful night scenery that makes the site a popular attraction. During the excavation of Wolji, the palace pond, some 30,000 artifacts were discovered that had been buried in the mud at its bottom. The Gyeongju National Museum carefully selected 1,100 items for permanent exhibition, categorized by theme. Relics excavated from the pond, including roof tiles depicting a dragon’s face, gilt-bronze Buddhist plaques, and gilt-bronze wick trimmers, offer a glimpse into the lavish lifestyles of Silla royalty and aristocrats.

The Daereungwon Ancient Tomb Complex in the Tumuli Park Belt consists of three main groups of royal tombs. Many artifacts were excavated here, including gold burial objects, glassware, and pottery. At Cheonmachong, the Heavenly Horse Tomb, a painting of a winged horse was discovered on a birch bark saddle flap, giving rise to questions as to who was buried there and guarded by the mythical animal.

Away from the city center is the Sanseong Belt, a series of ancient defensive fortresses around the east coast. Among them are the ruins of the Myeonghwal Mountain Fortress, with a circumference of about six kilometers, which was constructed with natural stones around the peak of Mt. Myeonghwal as an important bulwark against foreign invasion.

ESSENCE OF ANCIENT BUDDHIST ART

Buddhism is believed to have been introduced to Korea around the fourth century. Silla officially recognized it as the state religion in 527 following the martyrdom of Ichadon, a monk and advisor to King Beopheung (r. 514–540). Mt. Nam (Namsan), where different indigenous religions had been practiced, became a Buddhist holy mountain and pilgrimage site. Consequently, the most prominent architects and master craftsmen of the time built temples and hermitages there, and the Namsan Belt is thus home to the largest number of Buddhist relics in Korea, with scores of stone pagodas and Buddha statues still remaining.

For the Silla royal family, Buddhism was a means to achieve social cohesion, and Hwangnyongsa was one of the main temples built for the divine protection of the nation. It is famous for the nine-story wooden pagoda that once stood on its grounds, which, at 80 meters, was the tallest in the country. Today, only the temple site remains, from which around 40,000 artifacts have been excavated. Unfortunately, the wooden pagoda and many other cultural treasures were burned down during the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. The sites of the ancient temples Hwangnyongsa and Bunhwangsa comprise the Hwangnyongsa Belt, which represents the essence of Silla Buddhism.

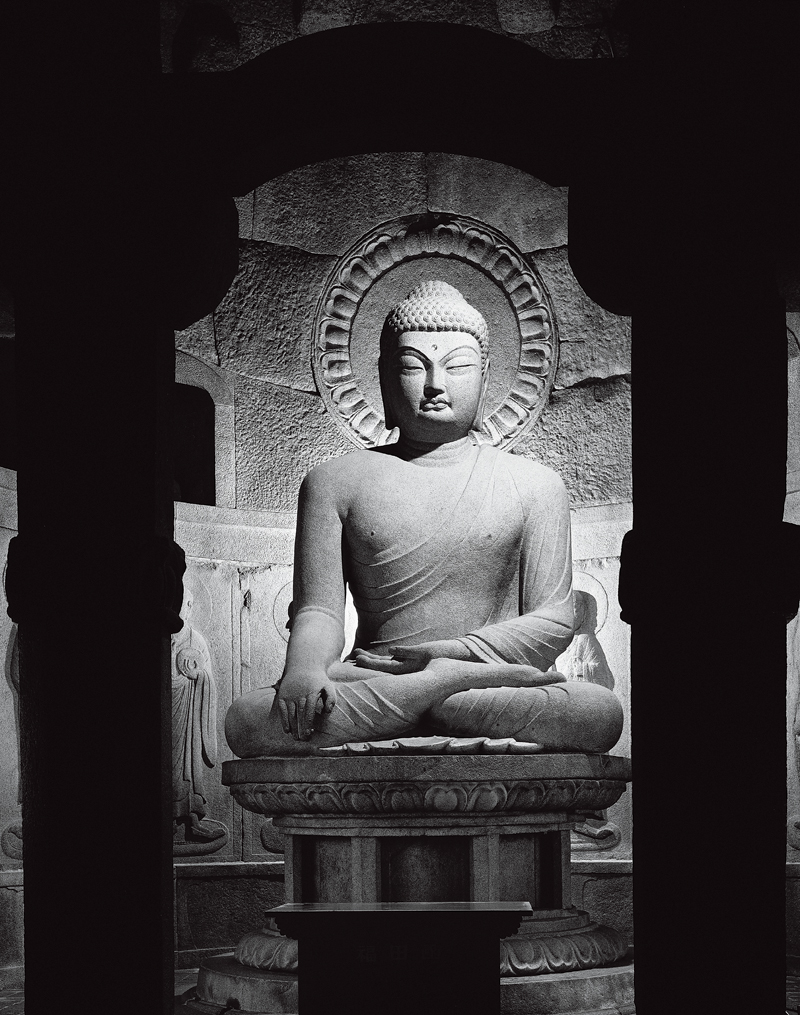

Located on Mt. Toham in southeastern Gyeongju are Bulguksa and Seokguram, an iconic temple and grotto, respectively, where some of the finest Buddhist art of Unified Silla can be seen. Both were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1995 and are recognized as the acme of Silla’s artistic achievement. Completed in 774, Seokguram retains its original form with a rectangular antechamber and corridor leading to the main rotunda, all decorated with exquisite bas-reliefs of the Four Guardian Kings and various bodhisattvas. In the main chamber is a 3.45-meter-high statue of the Buddha seated on a lotus flower-shaped pedestal.

A roof tile depicting a dragon’s face, excavated from Hwangnyongsa. Such decorative roof tiles expressed wishes for the dragon, a deity presiding over water, to protect wooden structures from fire. They originated during the Three Kingdoms period and production techniques reached their height during the Unified Silla period.

© Gyeongju National Museum

As you marvel at the Buddhist art, it’s not hard to see why Seokguram achieved the rare feat of meeting the first criterion of UNESCO’s World Heritage List: representing a masterpiece of human creative genius. Unlike marble, commonly used for sculptures in the West, the grotto was carved from granite, a material much harder to work with. This clearly demonstrates the technical prowess of craftsmen at the time.

Bulguksa is a manifestation of the Buddhist paradise. While it was a symbol of divine protection of the nation, like Hwangnyongsa, it also embodied the ambitious dream of creating the Buddhist Pure Land in Silla, a world liberated from the yoke of earthly anguish. The Silla people believed that their country was the land of the Buddha, hence Bulguksa was a temple that represented the Buddhist paradise in this world. The main worship halls, Daeungjeon (Hall of Great Enlightenment) and Geungnakjeon (Hall of Supreme Bliss), are reached by ascending Cheongungyo and Baegungyo, two bridges that together form a stairway. The bridges are the temple’s only structures remaining in their original form from the eighth century. Like Seokguram, the temple attests to the outstanding skills of Silla stonemasons. Two pagodas stand in front of Daeungjeon in clear contrast to each other — the minimalist Seokgatap, whose beauty comes from its perfect proportions and simple design, and the more relaxed and highly ornate Dabotap.

Seokguram and Bulguksa have endured a turbulent history. During the Imjin War (1592–1598), two Japanese invasions of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Bulguksa’s wooden structures were burned down. A major restoration project centering on the stone structures was first conducted in the 1960s and 1970s. Seokguram had been dismantled and restored during the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945), which paradoxically put it at risk of deterioration. It was not until the modern era that, with foreign assistance, full-scale repairs were conducted. However, Seokguram’s walls and ceilings continued to leak, so in 1960 the Korean government enlisted the help of international experts via the Korean National Commission for UNESCO. With their technical advice and financial support, urgent repairs were completed. Dr. Harold J. Plenderleith, a renowned Scottish art conservator and archaeologist who oversaw the project, recalled that the grotto was in grave danger of deteriorating beyond recognition. It almost seems like fate that Seokguram, revived with help from the international community, became one of Korea’s first World Heritage Sites.

FROM SCHOOL TRIP VENUE TO HOT SPOT

Gyeongju used to be a popular school trip destination for today’s middle-aged and elderly Koreans. It was always crowded with tour buses full of elementary school students from nearby cities, and middle and high school students from across the country. With enough to see and do for three days, it was worth enduring the long bus rides and the motion sickness that hit on the winding roads of Mt. Toham. At Poseokjeong, a pavilion site where Silla aristocrats once floated cups filled with alcohol on the water, you can hear the boisterous laughter of high schoolers imitating them.

Standing 9.51 meters tall, Cheomseongdae is an astronomical observatory from the Silla period where the movements of celestial bodies were observed. According to records, it was built during the reign of Queen Seondeok (r. 632–647) and provides valuable insight into the scientific advancements of the Silla Kingdom.

© Korea Tourism Organization

Today, Gyeongju has been reborn as a trendy destination for younger travelers. Being a treasure trove of cultural artifacts, the city put strict laws and policies in place to preserve its cultural heritage. This was once met with resistance and criticism, with residents complaining that the regulations were excessive when a wave of development swept through the city. But now, locals are taking an active role in protecting their neighborhoods and cultural heritage. It is thanks to such efforts that visitors can admire the ancient tumuli of Silla without high-rise buildings blocking the view and take in the breathtaking scenery from the pavilion at Wolji. The dazzling yet subtle night scenery is a bonus. Lighting at the historical sites allows visitors to explore them safely even at night, drawing young people wanting to snap instagrammable photos. The city that brings back fond memories of school trips for the older generation now creates lasting, magical memories for young folks.

Gyeongju is an ever-evolving city. New artifacts continue to be excavated while existing cultural heritage sites are continually being spruced up. The city’s streets are also changing with the times. The hanok street next to the ancient tomb complex is popular for its charming mix of traditional houses, cafés, eateries, and guesthouses. Steeped in history spanning a millennium, Gyeongju is a place where past and present coexist.

The city is also looking forward to the future, as it will host the 32nd Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit, scheduled to be held this November. Gyeongju is now preparing to welcome guests from around the world who will discuss the future amid the vestiges of the past.

Seokguram is a Buddhist cave temple built of granite on the mid-slope of Mt. Toham, Gyeongju, in the eighth century. Forty bas-reliefs of bodhisattvas surrounded the Buddha statue in the center, of which 38 remain today. The grotto was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1995.

© Korea Heritage Service

KIM Jihon Policy Team Head, Korean National Commission for UNESCO