Among Gyeongju’s many cultural treasures, the resplendent gold crowns and other gold regalia are not just magnificent artifacts — they attest to the interaction of the Silla Kingdom (57 BCE–935 CE) with peoples in the Eurasian steppes. The golden artifacts of Silla, which assimilated and reinvented elements from other cultures, are both universal and distinctive.

The exhibition Return of Cheonma was held at the Gyeongju National Museum in 2023 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the excavation of Cheonmachong. Showcased were 11 photographic works by Koo Bohnchang featuring gold artifacts and glass cups excavated from the tomb. Koo is renowned for the delicate sensibility with which he captures subjects embodying the traditional Korean aesthetic, such as white porcelain jars, traditional wooden masks, wooden dolls, and dancheong (traditional patterns painted onto wooden buildings). Lauded for elevating the artistry of contemporary Korean photography, he has recently been working on a series themed on Korea’s gold cultural heritage.

Courtesy of Gyeongju National Museum

Ancient Korea didn’t value gold as much as the rest of the world. Use of the precious metal, first discovered on the Korean peninsula around 2,000 years ago, started comparatively late. During the Three Kingdoms period (1st century BCE–7th century CE), gold was imported from neighboring countries. “Accounts of the Eastern Barbarians” from the Book of the Later Han, an ancient Chinese text, describes that time: “The people of Mahan [a political confederacy that existed in the southwestern region of the Korean peninsula] do not consider gold, silver, silk, or carpets precious. The only thing they value are beads [jade], which they use to decorate clothes or wear around the neck or on their ears.”

Koreans’ predilection for jade dates to the Neolithic Age. In dolmens built 3,000 years ago, more jade than bronze artifacts were discovered. In popular wisdom, many proverbs revolve around jade, and jade saunas and jade mats continue to be popular today.

Korea’s gold culture, epitomized by Silla’s gold crowns, began to flourish in Gyeongju in the fourth century. These crowns not only exhibit exquisite metal craftsmanship, they also shed light on interaction between Silla and the Eurasian steppes.

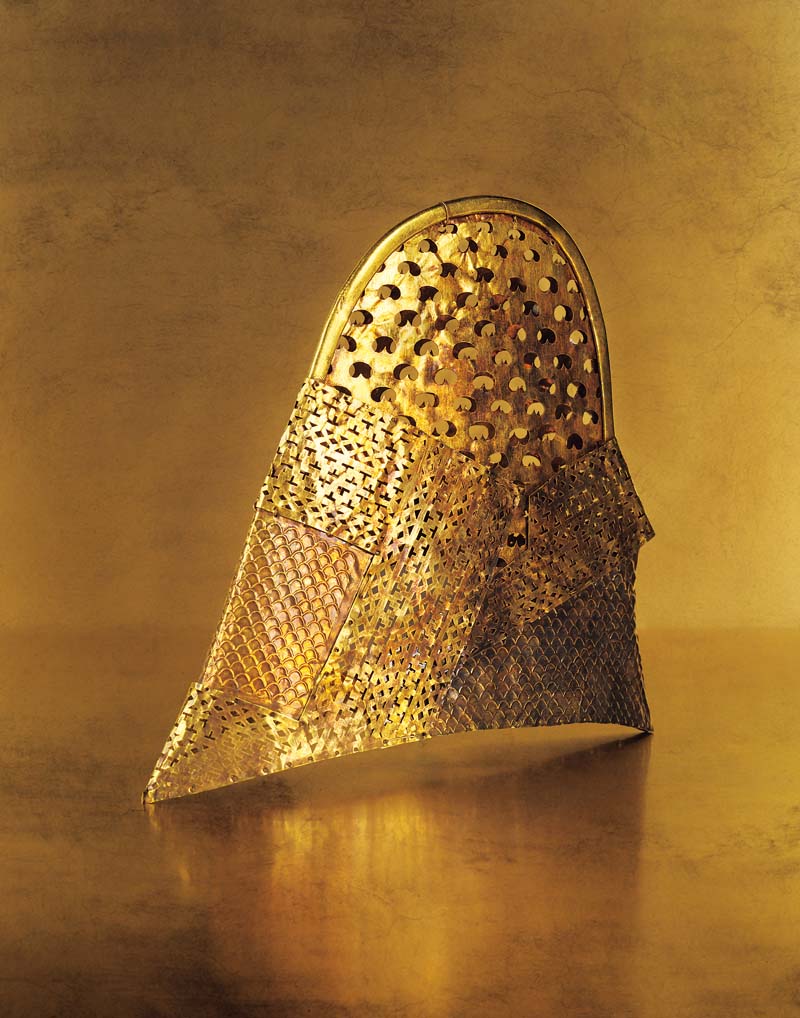

Gold (KR 043-1) by Koo Bohnchang. 2023. Archival pigment print. 58 × 45.5 cm.

This gwanmo, a triangular cap made from thinly cut gold plates that was worn inside a gold crown, was discovered in Geumgwanchong.

Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery

EXCAVATION OF GOLD CROWNS

The discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings in 1922 was a glob-al sensation. A year earlier, the discovery of a Silla tomb had garnered less attention but was also highly significant. The excavation yielded a gold crown, the first of its kind to be unearthed in Korea, earning the tomb the name Geumgwanchong (Gold Crown Tomb). Measuring 44 cm in height and 19 cm in diameter, the crown is the largest of the six gold crowns found so far.

Gold (KR 052) by Koo Bohnchang. 2023. Archival pigment print. 58 × 45.5 cm.

A gold crown that was excavated from Geumgwanchong. At the front of the headband are three branch-shaped uprights and at the back are two antler-shaped uprights. The crown exemplifies the style and shape of Silla gold crowns.

Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery

Unfortunately, the tomb, discovered by chance during construction work in Gyeongju, was excavated not by archaeologists but by non-experts under the direction of the Japanese colonial government. As a result, the discovered artifacts were not systematically docu-mented, so the exact number of gold artifacts retrieved and their original locations in the tomb are unknown. But the magnificent gold crown eventually became widely known, bringing global attention to Korea, at a time when it was still relatively unknown to the in-ternational community.

In 1926, another tomb was excavated to coincide with the visit of Crown Prince Gustaf and Princess Louise of Sweden. The crown prince, a keen archaeologist, participated in the excavation, which led to the discovery of another gold crown. Thus, the tomb was named Seobongchong, a combination of seo, the Chinese character for Sweden, and bong, referring to the phoenix decoration on the crown. This memorable event laid the foundation for the special relationship between Korea and Sweden. When Gustaf VI Adolf ascended to the throne in the early stages of the Korean War (1950–1953), he dispatched one of the first large-scale medical teams to the Republic of Korea, and to this day, a Swedish delegation is part of the commission that monitors compliance with the armistice on the Korean peninsula.

After the war, Silla’s gold crowns toured the world, serving as cultural ambassadors. In the 1970s, two further crowns were found during excavations of Cheonmachong (Heavenly Horse Tomb) and Hwangnam-daechong (Great Tomb of Hwangnam).

CULTURAL PARALLELS

Gold crowns excavated from the Scythian burial mound at Khokhlach on the Crimean peninsula and from Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan, dating to the period of mass migrations across Eurasia between the first and fifth centuries, revealed similarities to those from Silla. They share the tradition of gold art that originated from the Xiongnu, a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples that inhabited the Eurasian steppes.

Silla’s gold crowns display similar characteristics to the shamanic crowns seen throughout Eurasia. Although ritual headpieces worn by shamans, who acted as mediums between the physical and spiritual worlds, were typically made of iron or bronze, the deer antler and tree-shaped motifs are strikingly similar.

The imagery of deer antlers and trees as mediators connecting heaven and earth was commonly used on headgear throughout the vast Eurasian region, stretching from Europe to the Korean peninsula. Deer represent infinite life force because they grow new antlers every year, and trees reaching up to the sky signify the passageway to heaven. Even today, shamans across Eurasia perform rituals under sacred trees to communicate with divine spirits.

Until the early 20th century, the Manchus wore headdresses resembling Silla gold crowns when they conducted shamanic rituals in front of birch trees, which they considered sacred. Shamanic crowns were not merely ornaments but a medium connecting gods and humans. Petroglyphs found in present-day Siberia depict shamans wearing headgear that resembles a Wi-Fi receiver.

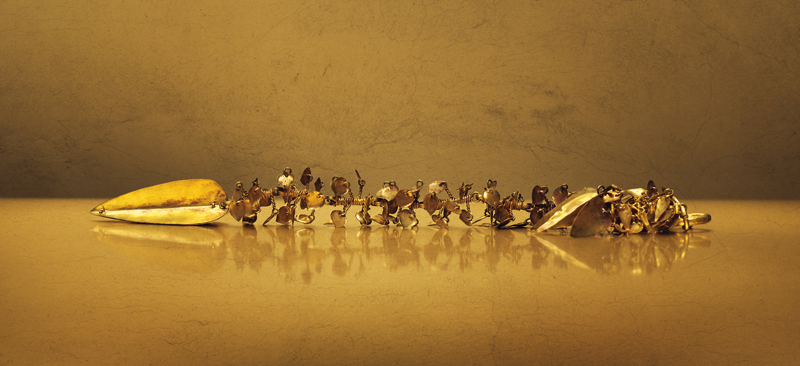

Gold (KR 50) by Koo Bohnchang. 2023. Archival pigment print. 64 × 140 cm.

This gold crown pendant, formed of intricate leaf-shapes joined closely together at regular intervals, was unearthed from Cheonmachong. It is an ornament that hung from either side of the crown.

Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery

The gold crown is also a symbol of a power monopoly. Three years after the discovery of the gold crown in Geumgwanchong, another tumulus was excavated and another gold crown found. This tomb was named Geumnyeongchong (Gold Bell Tomb) after the golden bells discovered among the relics, which also included earthenware funerary objects in the shape of warriors on horseback. Close inspection reveals that the warriors’ heads are pointed. This is evidence of the ancient practice of artificial cranial modification, whereby a hard , such as wood, is bound to an infant’s head to alter its shape. It was only performed on royal babies who would grow up to wear magnificent gold crowns and ornaments.

Gold (KR 48) by Koo Bohnchang. 2023. Archival pigment print. 58 × 45.5 cm.

In Silla, earrings were worn by women and men. This pair of earrings, 6.2 cm long, was discovered in Cheonmachong and is believed to have been worn by the tomb owner. Each consists of a ring, middle ornament, and heart-shaped pendant.

Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery

This custom was not confined to Silla. Across Eurasia, people who wore headpieces similar to Silla’s gold crowns exhibited cranial deformations. This is because shortly after the Xiongnu dominated the Eurasian steppes, the use of gold crowns and the custom of cranial modification became widespread.

Even to this day, the secrets of these gold crowns have not been fully revealed; likewise, Ko-rea’s gold crowns remain shrouded in mystery. In 2015, the National Museum of Korea re-excavated Geumgwanchong for additional research into the tomb. Judging from the inscriptions found on several artifacts, researchers concluded that the occupant of the tomb was most likely King Isaji. However, the true identity of King Isaji remains a mystery as there is no mention of the name in historical records.

SYMBOL OF NATIONAL POWER

The gold crowns of Silla feature an ornament that is not found on crowns in other countries: curved jade pendants called gogok. Though easily overlooked, this adornment contains the wisdom of the Silla people.

The exhibition Return of Cheonma showed photographic works by Koo Bohnchang that feature the gwanmo, gold crown, and gold diadem ornaments excavated from Cheonmachong.

Courtesy of Gyeongju National Museum

When gold was introduced to Korea, the people had to learn how to properly smelt the metal in furnaces. Naturally, the tools and labor applied to jade were not transferrable. But rather than choosing gold over jade, the Silla people combined the two. Korea’s jade and Eurasia’s gold merged to give Silla artifacts a distinctive appearance. Silla’s gold crowns represent the achievement of new aesthetic heights by harmonizing Eurasia’s gold-processing techniques and shamanistic symbolism with the East Asian tradition of gogok.

Of the three ancient kingdoms on the Korean peninsula — Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla — Silla was the last to develop into a full-fledged state. Initially, it was ruled alternately by three royal families — the Park, Seok, and Kim clans. Then, around the fourth century, during the reign of King Naemul, the Kim clan took over the monarchy exclusively. This also marked the beginning of Silla’s magnificent handling of gold. As Korean was written with Chinese characters at the time, the character for the family name Kim and the character for gold (金) became the same.

Gold was more than just a precious metal — it epitomized the power of Silla, which flourished through active exchange with other civilizations. Despite its geographical disadvantage, located in the southeastern corner of the Korean peninsula, Silla’s openness and receptiveness to cultural influences from Eurasia and Europe spurred its growth and allowed it to prosper for a millennium. This bears a resemblance to the economic and cultural achievements of Korea today.