A Korean film changed the course of Aya Narikawa’s life. It prompted a few measured steps and then a permanent move to Korea, leaving behind a successful newspaper career. Having recently completed a doctoral degree in film studies, she is now more committed than ever to fostering cultural exchange bet

ween Korea and Japan.

Aya Narikawa, a former Asahi Shimbun journalist turned film columnist, poses inside Indiespace near Hongik University Station in Seoul. She watches an average of four Korean films a month, and her interest in indie films often draws her to this theater.

Some aspects of a film only come to your attention when you watch it several times. In 2021, Aya Narikawa attended a 20th anniversary screening of Take Care of My Cat, a Korean coming-of-age film, directed by Jeong Jae-eun, about recent high school graduates entering adulthood. Watching it again after all those years was a wake-up call. Narikawa realized, “The protagonist is a lot like me in that she wants to experience a different world. I was like that in my early twenties.”

When the film debuted in 2001, Narikawa had no real urge to travel far. Born in Osaka and raised in Kochi on the island of Shikoku, she neither wanted to leave Japan nor be apart from her family. Yet, deep down, she had always wanted to live somewhere else, as a different person.

Her wish came true in neighboring Korea. Narikawa first arrived in Seoul in 2002 to enroll in Korean language classes, and three years later, she returned as an exchange student. Then, in 2017, she made a bold decision to leave her newspaper job in Japan to fully immerse herself in Korean cinema, one of her long-time interests.

CONNECTING CULTURES

Influenced by her grandfather, who ran a movie theater, Narikawa grew up watching films with her mother. Her fascination with Korean cinema deepened after her language studies in Seoul.

Narikawa graduated from Kobe University’s Faculty of Law but turned to journalism, embarking on a nine-year career at the Asahi Shimbun. As a reporter on the newspaper’s culture desk and a fluent Korean language speaker immersed in Korean cinema, she positioned herself as a bridge between Japan and Korea. She interviewed visiting Korean filmmakers and acted as an interpreter. But Narikawa found herself wanting to do more.

“From the early 2000s, Korean dramas and K-pop became huge in Japan, but Korean films were not as popular. When Snowpiercer opened in Japanese theaters, I interviewed the director and requested a long feature in the paper because it was none other than Bong Joon-ho. I remember being very disappointed when the desk editor asked who he was. Instead of waiting for the opportunity to write about Korean films to my heart’s content, I decided to take matters into my own hands and came to Korea to study.”

Despite concerns from those around her about quitting a stable job to return to student life, Na-rikawa was undeterred. She enrolled in a master’s program in film and digital media at Dongguk University in Seoul.

UNSPOOLING KOREA

A Korean journalist fascinated by Narikawa’s story invited her to write a column for the JoongAng Ilbo, and she gladly seized the opportunity. For several years now, she has written about Korean culture from a Japanese perspective. Based in Ilsan, Gyeonggi Province, she has chronicled her travels to Busan, Jeonju, and Jecheon, among other cities. She said her favorite place is Jeju because she both admires its natural beauty and recognizes the historical scars the island carries.

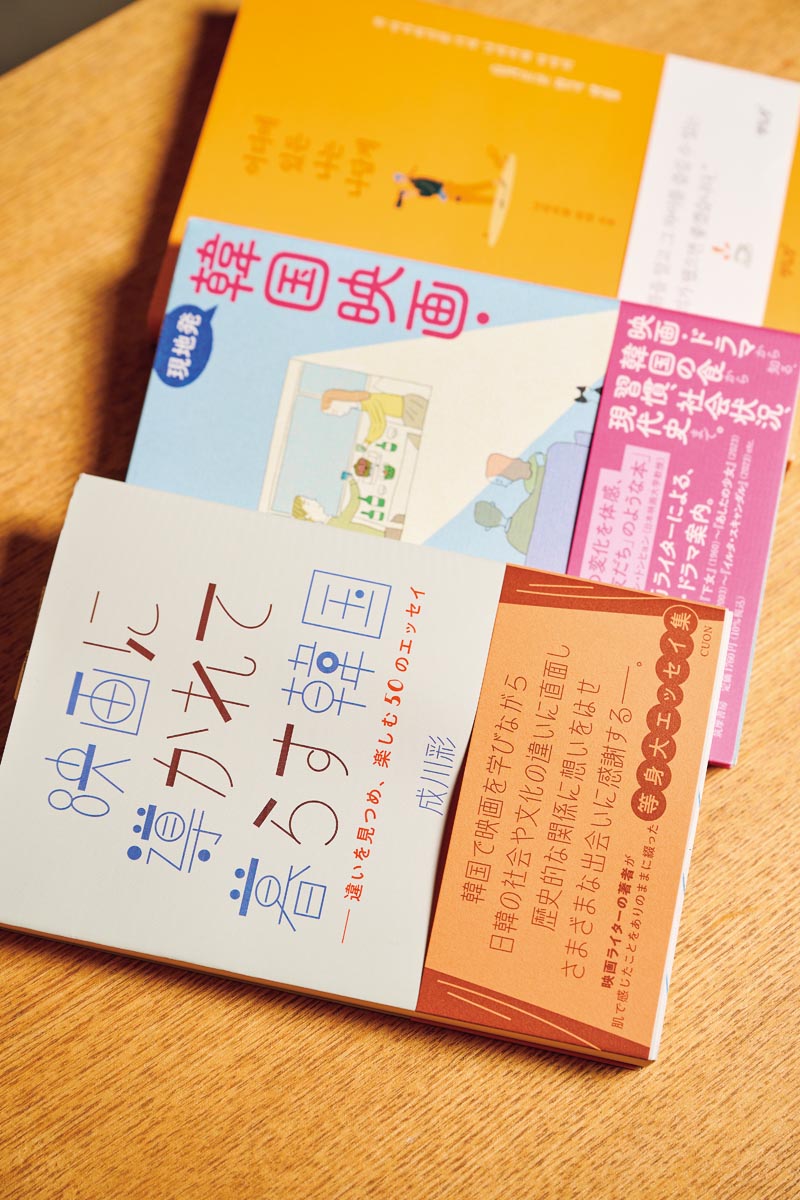

The books Narikawa recently published in Korea and Japan. It is her dream to one day operate a book café in Korea where she can introduce Japanese books and indie films.

Narikawa fondly recalls sighting dolphins off the Jeju coast but says her visit to the Jeju 4·3 Peace Memorial Hall with her family was especially memorable. She first learned about Korea’s democratization movement through Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy (2000). Her understanding of modern Korean history deepened through films like Jiseul (2013), directed by O Muel, The Battleship Island (2017) by Ryoo Seung-wan, and 1987: When the Day Comes (2017) by Jang Joon-hwan.

Narikawa says that learning another country’s history through film can be more effective than simply memorizing dates and events from a textbook. Fortunately, she was able to participate in a research project on Zainichi (ethnic Koreans living in Japan) at the Institute of Japanese Studies at Dongguk University, and she remembers the pride she felt when the institute hosted the Zainichi Film Festival in 2019.

In February this year, Narikawa obtained a doctoral degree, with her dissertation titled South Korea–Japan Film Exchanges Since the Normalization of Diplomatic Relations. This topic was a natural choice, given her extensive contributions to Korean and Japanese media about Korean film and her TV appearances promoting the cultures of both countries.

The dissertation includes examples of key Korean figures working in the Japanese film scene, such as the late cinematographer Lee Byung-woo and Lee Bong-woo, the founder of Cinequanon, a distributor of Korean movies. Both were pioneers in cultural exchange at a time when collaboration between the two countries was rare. Narikawa reminded herself, “Even during more challenging times, cultural exchange still happened. Learning how they made it work back then gives me the courage to find new ways to continue their legacy.”

A particularly serendipitous moment during her research occurred when she had dinner with a journalist from the Asahi Shimbun and unexpectedly met Lee Byung-woo’s granddaughter. Finding records on Korean film professionals in Japan had been incredibly difficult, but through this chance encounter she was able to gain access to valuable documents.

“Maybe it’s the skills and intuition from my years as a journalist, but sometimes, when I really need to meet someone or find certain materials, they just appear. Moments like that have helped me navigate life in Korea,” she says.

DREAMS OF A BOOK CAFÉ

After successfully defending her dissertation, Narikawa traveled to Tokyo with a light heart to attend a book talk on Being Me Wherever I Am, a collection of her columns published in Korea in 2020 and in Japan last October. The event was held at Chekccori, a Korean bookstore in Jimbocho Book Town, in Tokyo’s Chiyoda ward. The staff at the bookstore gave her a certificate of appreciation for her efforts in fostering cultural exchange between Korea and Japan, featuring a quote from her mother asking her to “become a person who can enjoy being different.”

At the book talk, Narikawa received enthusiastic support from her readers. Having listened to their questions, she said she thought about her plans five years from now.

“Maybe the reverse of Chekccori is possible? In other words, I would like to operate a book café in Seoul introducing Japanese books and films, and hold screenings for Japanese indie films not shown in Korean cinemas. If I keep talking about the idea, maybe someone will appear to help make it happen.”

Narikawa’s website, where she posts snippets of her daily life along with her film columns and newspaper articles.

Captured from Narikawa’s website

Her Japanese friends, once worried about her career shift, now tell her she looks genuinely happy. She smiles to herself, imagining her own book café, and says, “I never try to put on a happy face intentionally, but hearing what my friends say surprises me.” Perhaps her happiness comes naturally from studying what she likes and sharing that knowledge through her talks and writings.

“I would be lying if I said life away from home wasn’t difficult. But only those who step outside their comfort zones to pursue what they truly want can seize new opportunities. Once you try, you can discover something bigger than you had ever imagined!”