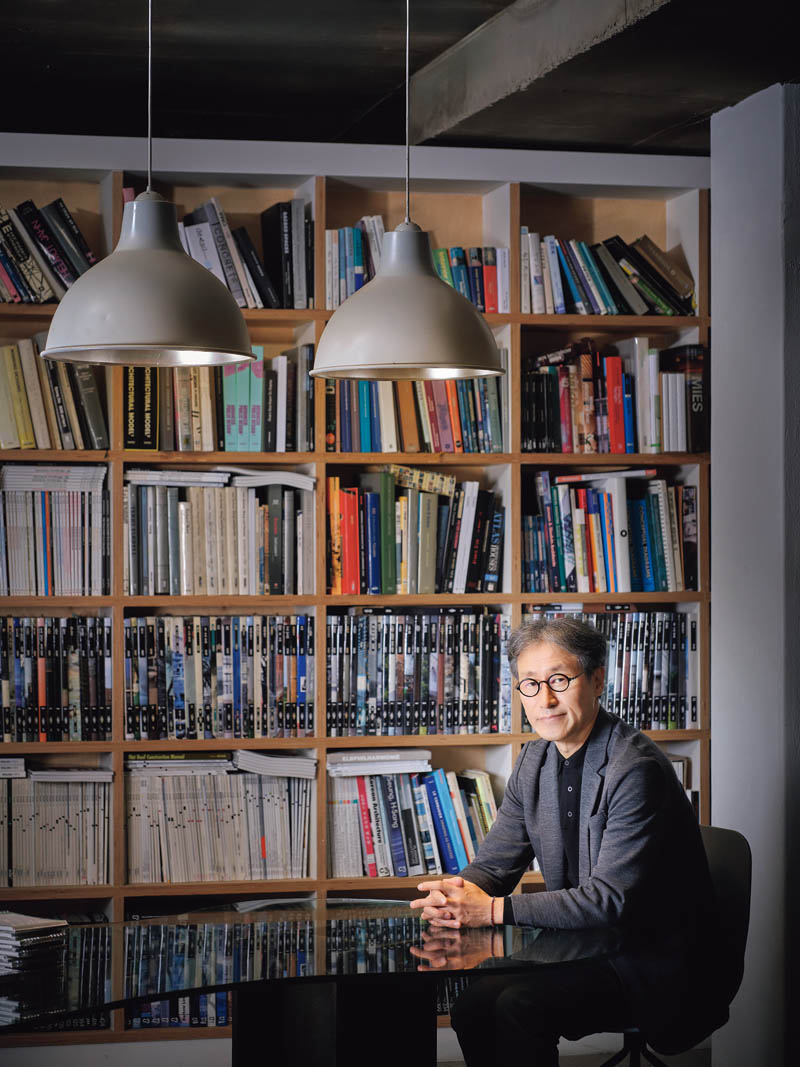

The works of Cho Namho are said to make people think about the influence of architecture on people’s lives. Founder of Soltozibin Architects, Cho believes that the combination of good planning and technology leads to new architecture and has long pursued the possibilities of building with wood.

Architect Cho Namho took advantage of the porosity of wood cell walls to design the exterior of Breathing Folly, a project that addresses the question of whether tackling the current climate crisis can be a central agenda for architecture.

© Yoon Joon-hwan

Cho Namho has continuously explored new possibilities in wooden architecture by employing innovative construction methods. Before founding Soltozibin Architects in 1995, he had grown accustomed to designing relatively large buildings while training at a major Korean design firm. However, when the 1997 Asian financial crisis put his young architectural firm at risk, Cho abandoned the traditional approach to securing contracts. Instead, to navigate the crisis, he transformed the company into a learning organization. As a result, Soltozibin Architects evolved into a forward-thinking institution, sharing ideas on the future of architecture and conducting extensive research on new production systems. Naturally, the firm also thought about a clever financial strategy.

During this period, Cho began focusing on the potential of wooden architecture. Rather than overseeing the segmented labor involved in reinforced concrete construction, he much preferred working directly with carpenters in the process of wooden construction.

It also appeared that the domestic market for wooden architecture, which relied heavily on traditional techniques, was in need of modernization. With industrialization, wooden architecture in Korea had all but disappeared, apart from a small number of hanok, or traditional houses. Around the time he founded Soltozibin — named after a term from the Classic of Poetrymeaning “the whole world” — North American-style light wood frame construction was introduced to Korea and wooden houses started to be built in new towns such as Ilsan in Gyeonggi Province. However, since this was merely an import of the North American model, many challenges remained, including issues related to logistics and construction costs. Despite these barriers, Cho believed that many aspects of modern architecture could be applied to wooden structures. He saw vast potential for expansion of the field, driven by economic feasibility, environmental concerns, and architectural innovation.

Cho explores the relationship between architecture, society, and everyday life. By applying modern construction methods to wooden structures, he has produced various works that emphasize harmonious coexistence between humans and the environment.

© Studio Kenn

TRANSFORMATION AND EVOLUTION

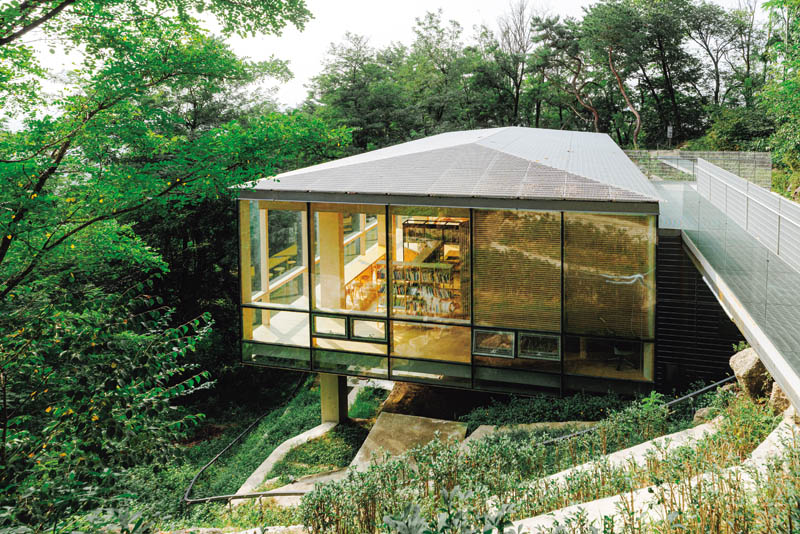

With every project, Cho’s exploration of new architectural production systems has changed and further evolved. It all began with the Sinwon-dong project, completed in 1999. Situated on the boundary between Seoul and the greater metropolitan area, Sinwon-dong is an area of high-rise buildings with pockets of arable land used for growing fruit and vegetables. With a nod to these local characteristics, Cho designed a house that brought together urban and suburban living. He also took charge of constructing the hybrid structure of reinforced concrete and wood, which made the entire project a great challenge.

KYOWON Group Guesthouse, one of Cho’s early projects, garnered significant attention in the architectural community and earned his firm the Korean Architecture Award in 2000. Unusually large for a wooden project, it comprises ten houses built with a variety of construction methods, including heavy timber framing. At the time, no domestic companies were capable of handling the structural engineering, so Cho collaborated with firms from Canada and New Zealand. Inspired by seowon, Confucian academies of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), the project pursued a third way, namely a synthesis between traditional and modern wooden construction methods.

A reinforced concrete structure, the Architectural Engineering Building at the University of Seoul (2005), introduced a wood-wall system utilizing platform frame construction. Here the platform frame is multifunctional: it serves as the structural framework, houses insulation materials, and functions as the base for finishing materials. Reflecting on this building, Cho remarks, “Focusing on the incredible efficiency of wooden structures frees you from the obsession of revealing structural beauty through the post-and-lintel system, such as in traditional hanok.” This project marked a shift in Cho’s approach, expanding construction methodology into a form of architectural .

For the University of Seoul Gangchon Training Center, Cho employed wood joinery methods to experiment with a new wooden architectural style. Praised as a beautiful building that maximizes the benefits of wooden construction, it received the Korean Institute of Architects Award in 2011.

© Park Young-chae

In the University of Seoul Gangchon Training Center (2009) in Chuncheon, Gangwon Province, all structural members are standardized, meaning that elements such as columns and beams were designed with uniform widths and lengths, despite their different functions and conditions. This consistency gave the building a sense of integration and order. It also required a complex structural strategy employing truss principles. Modern architecture often deconstructs the center, removing symbolic elements and making all spaces equally significant, a characteristic embodied by the Gangchon Training Center.

In the relatively new Inwang Guard Post Forest Retreat (2019), the connections of the posts and lintels — core elements of traditional wooden structures — were not exposed, but roof panels were inserted between the posts, creating the illusion of massive floating boards. The structurally joined yet visually disconnected elements create a constructional paradox. Generally, a post-and-lintel structure forms a completed frame, but in this building Cho deliberately created joinery that appears unjoined and directs attention not inward but outward toward the surrounding nature.

The Inwang Guard Post Forest Retreat takes a different approach from traditional wooden construction methods. The architect erected wooden columns at half the interval of the reinforced concrete piloti column modules and inserted roof panels in between.

© Shin Jung-sik

ARCHITECTURE THAT BREATHES

The concept of “breathing” frequently appears in Cho’s writings and interviews. A good example is the Breathing Folly (2023) building that the architect presented at Gwangju Folly, an urban regeneration project addressing the decline ofGwangju’s old city center. When asked about the meaning of breathing in architecture, he gave two answers.

First, the building’s exterior allows for natural ventilation, and hence it breathes in a literal sense. However, this contradicts modern insulation requirements. Historically, modern architecture has been insulated and made airtight, removing heat and pollutants to make the interior more pleasant after separating interior and exterior spaces. This method is followed in insulation, waterproofing, and air sealing, particularly in concrete buildings. In the walls of Breathing Folly, Cho used breathable materials and joinery techniques that facilitate air circulation. The project was a way of exploring how a material as structurally vulnerable as wood could respond to the emphasis on strength in modern architecture.

Ecological Matrix, Breathing Net, an outdoor theater at Seoul Forest, was created as part of a public art project. Cho stacked wooden units in a grid formation at one-meter intervals, creating voids in the walls that serve as shelters for birds and allow grass and flowers to grow.

© Yoon Joon-hwan

Second, the architect defines breathing in his work as architecture that causes minimal damage to the surrounding environment throughout its entire life cycle — from conceptualization, material selection, and detail planning to construction, use, maintenance, and eventual disposal.

Breathing Folly fulfills both definitions: it is a breathing structure in both function and form. The wood absorbs and releases moisture, while the interplay between exterior and interior spaces creates the visual impression of a breathing building. Furthermore, carbon emissions for this structure have been reduced to one-tenth of those produced by conventional concrete buildings. If a photovoltaic system were to be implemented to offset additional emissions, the facility could become completely carbon-neutral within 15 years.

Dasan-dong Complex, located in Jung-gu, central Seoul, provides a glimpse at Cho’s experimentation with residential space. The first and second floors are designed in the style of galleries, exhibiting the homeowners’ art collection and serving as spaces of communication and exchange.

© Kim Yong-kwan

CRITICISM AND EXPLORATION

Aristotle emphasized technē (technology) as the foundation of theoretical and practical knowledge and the source for the creation of new things.

Based on these beliefs, Cho has sought to apply wooden construction to modern architecture for the past 25 years. Despite his efforts, the development of Korean wooden architecture has been slow, which he attributes to rigid adherence to the traditional hanok style. In the distant past, Koreans created architectural masterpieces, such as the Nine-Story Wooden Pagoda of Hwangnyongsa, a seventh-century temple, and Seokguram, an eighth-century Budhist grotto in Gyeongju. However, since the Joseon Dynasty, there has been a noticeable lack of innovation in wooden architecture — a stark contrast to other parts of the world that have seen almost perennial evolution in their respective architectural types.

Since ancient times and in particular the medieval age onward, many countries have cultivated highly skilled artisans and engineers whose expertise has often rivaled that of scholars. During the Joseon period, however, technology was held in low regard, rendering innovation difficult. This lack of progress was further exacerbated during the Japanese occupation (1910–1945), when formal architectural training was virtually nonexistent.

Cho argues that Korea’s architectural practice must move beyond the conservative constraints of hanok-centric policies, pointing out that other wooden architectural options exist. To revitalize Korean wooden architecture, he emphasizes the need for constructive criticism among architects as well as technological exploration and improvements that foster innovation.