Veteran movie director Jéro Yun tries to shed new light on people living today, without stereotypes or prejudice. This is also why he makes both ary and dramatic films.

Award-winning film director Jéro Yun applies cinematic skills honed in France to delve intothe lives of those on the margins of society, particularly North Korean defectors.

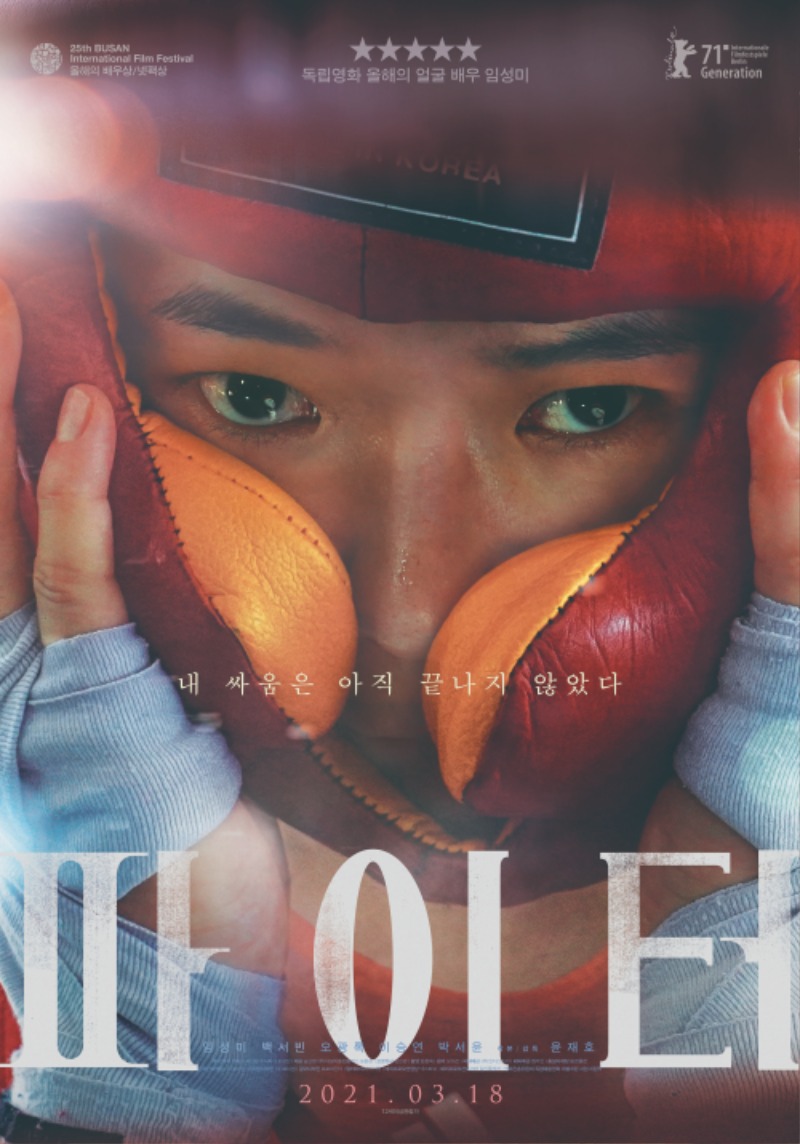

Film director Jéro Yun, released two full-length films in 2021: “Fighter,” a drama, and “Song Hae 1927,” a ary. The former is about Jin-a, a young North Korean defector who faces discrimination in the South and struggles to save money. She does menial work in a restaurant and takes on a second job cleaning at a boxing gym, where she is inspired by the sight of confident female fighters. The latter is about Song Hae (1927-2022), the late singer and host of KBS TV’s long-running music show “National Singing Contest,” who fled from his native town in Hwanghae Province, North Korea during the Korean War.

These films tap into the deep emotions and scars of defectors’ hearts. Jin-a learns how to box, but “Fighter” is less about her bouts than her struggle to adapt to living in South Korean society. As for Song, he talks candidly about his only son, who died in a motorcycle accident in 1986.

A Defector’s Life

Throughout his directing career, Yun has gazed into the lives of those on the margins of society, particularly North Korean defectors. His works are cool-headed observations of the inner side of characters, attracting attention at top Korean and international film festivals.

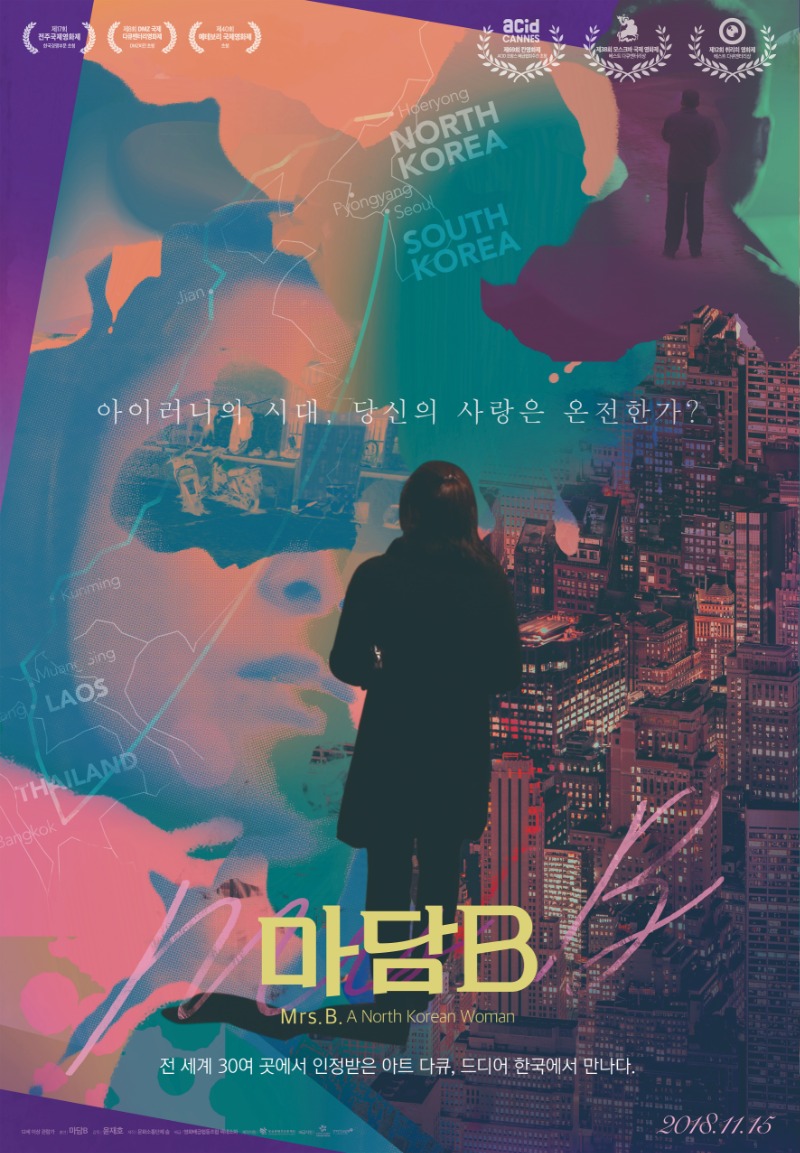

In 2011, Yun won the Grand Prix at the 9th Asiana International Short Film Festival with “Promise” (2010), a ary about a Korean-Chinese woman who never stops hoping to reunite with her son. He also won awards for best ary at the 38th Moscow International Film Festival and the 12th Zurich Film Festival with “Mrs. B, A North Korean Woman” (2016), whose protagonist goes to China to make a living.

“Mrs. B” is related to “Beautiful Days” (2017), Yun’s first full-length film starring actress Lee Na-young. The opening film at the 23rd Busan International Film Festival, “Beautiful Days” is about how Zhenchen, a Korean-Chinese college student, regards her North Korean mother. Yun has also introduced various features of lifestyles in the two Koreas to filmmakers. He showed his short film “Hitchhiker” (2016) at the 69th Cannes International Film Festival Directors’ Fortnight, and “Fighter” in the 71st Berlin International Film Festival’s Generation Section.

Student in France

When Yun was in his early 20s, he went to France with a friend to satisfy his desire for a totally new environment. The day of his departure was memorable on a level that was more than just personal – it was September 12, 2001, the day after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States. Airport security was on heightened and all flights to the United States were canceled.

Yun managed to make his way to Nancy, a small town in northeastern France. Once there, he traveled and learned to speak French. Suddenly, without any preparation, he decided to apply for a local arts school and passed the practical skills enrollment test. Becoming a full-time student outside of Korea was totally unplanned, but he overcame his apprehension and reveled in being impetuous. “I was afraid of living a new life all by myself in an unfamiliar place. But it was fun. I was able to think only of myself at the time,” he says, looking back.

The experience expanded his horizons. At school, he took courses in video and installation arts, while outside, interaction with classmates from other countries further widened his scope. When a Belgian friend lent him a box of 100 DVDs, Yun found himself in a cinematic world that was totally new to him.

Inside the box were classic movies of the 1950s and 1960s made by legendary directors such as Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Ingmar Bergman and Orson Welles. Up until then, Yun had only seen movies brimming with violence, but before him, for the first time, were movies with intellect and experimentation. “I watched all 100 of the DVDs over and over. It was hard to understand them, but they were that mesmerizing,” Yun recalls.

What beguiled him most was the fact that filmmaking is a process that cannot be done alone. Needing input from many people, Yun assembled friends to pick their brains and collaborate.

“Mrs. B, A North Korean Woman” is a full length ary about the life of a North Korean woman who has crossed into China to make a living.

© CINESOPA

“Beautiful Day” is the first full-length dramatic film Yun directed. It explores how protagonist Zhenchen, a Korean-Chinese college student, regards her North Korean mother.

© peppermint&company

“Fighter” is a movie about Jin-a, a young North Korean defector who struggles to survive financially and adapt emotionally to her new life in South Korea.

© INDIESTORY

Life Today

Yun and his friends introduced their first joint movie in 2004. Its protagonist was a South Korean woman in France questioning her identity. “Why do I live here?” “Why here and not there?” These were tormenting questions that Yun had asked himself. Fittingly, the budding filmmakers invited other foreign transplants to a preview of the movie. From that point on, Yun’s self-questioning about his life in France morphed into a sustained interest in the life of defectors from North Korea.

When formulating his works, Yun focuses especially on his marginalized characters in the context of time. He delves into their past to see how their experiences shape their present behavior and thinking.

“Though we live today, today eventually becomes yesterday. And tomorrow can change depending on how we live today. So I usually leave out people’s past stories and try not to cling to their future, either. I just want to show how they’re living today. If the me of today changes, the me of tomorrow will surely change as well. That’s the message I want to deliver,” Yun says.

This principle applies equally to his ary and drama films. For three years while making “Mrs. B,” he traveled together with Mrs. B herself. On the first day of shooting “Song Hae 1927,” he interviewed Song for more than four hours.

In his movies, Yun attempts to express the little things that he feels from observing moments in daily life. “What do defectors think of?” “What do they feel here in South Korea?” Yun and the actors repeatedly ask themselves such questions. In addition to conferring with defectors, the actors try to bring their personal experiences into their scenes, while Yun filters out stereotypical images of defectors often seen in the media.

“Song Hae 1927” vividly shows the life of Song Hae, the late singer and host of KBS TV’s long-running music show “National Singing Contest.”

Questions, not Answers

Yun makes films that pose questions to viewers. He does not supply answers. His films normally end with a palpable possibility for the future instead of a denouement. Will the hopes of the mother and her son in “Beautiful Days” be realized? Will Jin-a win a boxing match in “Fighter”? Yun always leaves the audience dangling. But he hints that the characters may wind up living a tomorrow that differs from yesterday. In this way, his characters gain some dignity at the margins of society. “Everyone has a different definition of happiness. I want to give my film characters as much of an open ending as possible. This way, the audience will begin to think hard about how defectors can be happy in South Korea, won’t they?” he asks.

Audience reactions to Yun’s films run the gamut, largely depending on the viewer’s personal experiences. Defectors have mixed reactions; some feel embarrassed at the true-to-life depiction of their fate while others express gratitude, thanking the filmmakers for listening to them and absorbing what they heard. Human rights activists and students studying the reality of a divided Korea have differing impressions based on their own background knowledge. For foreign viewers, the films are more of an eye opener on the way the Korean peninsula has been divided into totally different spheres marked by separation and animosity.

“I just want my films to be of value, even if it’s to one single person. Nobody knows what kind of work that person could do later, or where,” Yun said.

Yun makes films because he believes in the power of every individual, including himself, to influence others. When asked what motivates him, he said that it is “love.” “If there’s a problem somewhere, be it war or national division, there is surely a lack of love.”