Ryoo Seung-wan’s

I, The Executioner, the sequel to his 2015 blockbuster

Veteran, questions the distinction betw

een good and evil when a vigilante takes justice into his own hands. Here, the director talks about the film in an interview at the Cannes Film Festival.

Ryoo Seung-wan is a renowned filmmaker who captures the darker side of Korean society and human nature with sharp insight to create works that resonate with diverse audiences. His signature style combines dynamic action, powerful character-driven narratives, and a seamless blend of social commentary and entertainment.

Photo courtesy of CJ ENM

Director Ryoo Seung-wan has been a pillar of the South Korean film industry for more than twenty years. Renowned for his action films, keen observations, and intelligence in addressing social issues, Ryoo delivered a box office sensation last year with Smugglers. It followed the twists and turns of a group of haenyeo, female divers, whose livelihood of harvesting marine life is threatened when a chemical plant opens in their quiet seaside town.

This year, he brings back the police detectives from Veteran to pursue a suspected serial killer. I, the Executioner (a.k.a. Veteran 2) hit Korean theaters in September, just before the mid-autumn Chuseok holidays, and attracted more than 7.5 million viewers across the country.

The original Veteran grossed over USD 90 million at the South Korean box office, making it the fifth-highest-grossing film in the country’s history. Its success crossed borders, inspiring an Indian remake in 2019, with superstar Salman Khan starring in the lead role. American filmmaker Michael Mann is currently developing another remake, scheduled to be filmed right after his much anticipated Heat 2 project. The first showing of Veteran outside Korea was at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). The sequel premiered at this year’s Cannes Film Festival in the prestigious Midnight Section at the Grand Théâtre Lumière.

Cannes has had a roster of Korean films in its official selection. Previous attention-getters include Kim Jee-woon’s The Good, the Bad, the Weird; Han Jae-rim’s Emergency Declaration, Na Hong-jin’s The Yellow Sea, Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden; Yoon Jong-bin’s The Spy Gone North; and, most prominently, Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite, the 2019 Palme d’Or winner.

Ryoo Seung-wan first attended Cannes in 2005 with his boxing drama Crying Fist. Featured in the Directors’ Fortnight, it starred his younger brother Ryoo Seung-bum, now a major star, alongside Korean film icon Choi Min-sik, who was then already a familiar face to global audiences thanks to his performance in Park Chan-wook’s Old Boy, winner of the Grand Prix at Cannes in 2004.

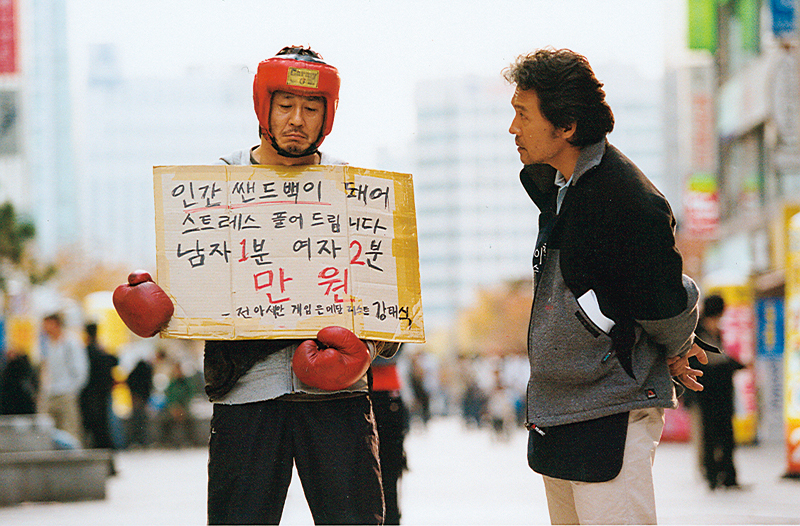

One of Ryoo’s early works, Crying Fist (2005), is about a former boxing star and Asian Games silver medalist struggling to find a new path in life. Stripped of flashy techniques and action, the film focuses deeply on the characters’ inner struggles and emotions.

Photo courtesy of Yong Film

The original Veteran starred Hwang Jung-min as an irreverent and relentless police detective tasked with bringing down a corrupt and sadistic third-generation tycoon, played by the unforgettable Yoo Ah-in. The film masterfully blended humor, intense action, and a scathing critique of corruption and inequality in Korea, which resonated deeply with the audience. The sequel reunites Hwang with the original film’s dynamic ensemble cast — including Oh Dal-su and Jang Yoon-ju. New to the team is Jung Hae-in, who joins the Violent Crimes Investigation Squad. As rumors about the killer’s identity spread like wildfire on social media, plunging the country into chaos, the hero detective and his team must weigh their methods and assumptions.

A scene from Ryoo’s latest film, I, The Executioner (Veteran 2). Released domestically in September 2024, the film became a box office hit, drawing over 7.5 million viewers across the country.

Photo courtesy of CJ ENM

How was your recent Cannes experience, compared to the first one in 2005?

The biggest difference is that nineteen years ago, I was just an outsider looking at the Grand Théâtre Lumière from afar. I was much younger, and everything felt fresh, new, fun, and exciting. I remember thinking to myself, One day, I would love to screen my film in this theater. Now, I was inside, presenting my film. Another significant change is the recognition that Korean cinema receives today. Nineteen years ago, Korean films didn’t get nearly as much attention. Theaters weren’t packed, nor were there as many interview requests as we receive now.

What drew you to action films?

I loved cinema even before I went to school. I grew up in Asan, which wasn’t a big city but had a strong cultural presence. I had access to a variety of films — from Hollywood blockbusters to Asian productions, including Hong Kong cinema. I was captivated by Hong Kong martial arts movies and their incredible stars. My impressions of these action heroes became ingrained in me, shaping my understanding of cinema as an art form that captures movement and gestures. However, as I’ve grown, my approach to action has evolved. Now, when I say “action,” it encompasses much more than just physical movements or body language. It involves the evolution of characters, their psychology, the unfolding events, and how the audience’s emotions and thoughts shift with the story.

Ryoo’s fifth feature film, The City of Violence (2006), stars the director himself and his longtime friend and collaborator Jung Doo-hong (left), a martial arts director and action star. Famous for its intense, unassisted hand-to-hand combat scenes, it showcases raw action without relying on wirework.

© Cine21

What do you think made Veteran such a success? Why did you revisit the story nine years later?

The success of the first film was a big surprise to me, and to be honest, I had a hard time handling it. Initially, I wanted to make a genre film that was true to my style, offering joy and escape for the Korean audience. Coincidentally, at the time, some social controversies emerged that mirrored the events in the film, which turned it into a box-office phenomenon. While filming Veteran, I became attached to the characters, which made me want to revisit their story. However, the film’s success actually held me back from diving into the material right away. In the first film, the depiction of good and evil was maybe a bit too straightforward. This simplicity might have contributed to its success, but looking back, it feels a bit superficial. The way the protagonist sought justice was quite different from the complexities of real life. In reality, the distinction between good and evil isn’t always as clear. After Veteran’s success, many Korean films and TV series followed in its footsteps and also found success, so I didn’t feel an urgent need to replicate my earlier work. In the meantime, I made several other films, including the political thriller Escape from Mogadishu, which was South Korea’s official submission to the Oscars in 2021. Nine years have flown by quickly, and I felt it was finally the right time to return to Veteran with a fresh approach.

Released in 2013, The Berlin File depicts a high-stakes chase in an international conspiracy. Praised for its stellar cast, inventive action, and tightly woven storyline, the film is regarded as a milestone in Korean action cinema. Actor Ryoo Seung-bum, who is also Ryoo Seung-wan’s younger brother, is often referred to as the director’s persona. © CJ ENM

How would you define Park Sun-woo, the controversial figure in the sequel?

I intentionally infused the character and the story with controversy, and I want the audience to react — whatever their reaction may be. If the controversy resonates with them personally, it means they are reflecting on it, and that’s exactly what I aim for. I once met the great Hong Kong filmmaker Johnny To and asked him how I could make films as engaging and entertaining as his. He told me, “Your protagonist has to make mistakes.” His answer was simple and clear, and I loved that idea.

In most films, those who take justice into their own hands are usually punished in the end. In your film things aren’t quite as simple.

That’s an interesting point. In my film, the actual protagonist is not Park Sun-woo but the detective Seo Do-cheol. The beauty of Seo’s character, and what sets him apart from Sun-woo, is that even if he hates someone to the point of wanting to kill them, he remains loyal to his duty. He would save a person’s life, even if that person were a criminal. To him, that is what real justice means. As for Park Sun-woo, I did not intend to portray him as a traditional villain. My goal was to explore two different concepts of justice and the conflict between them. The definition of justice is defined by perspective and historical context, and how they are applied. I don’t believe in absolute justice or absolute truth. I want the audience to question their values rather than imposing specific messages on them.

How does the sequel’s storyline differ?

When you talk to people, there is always this impression that past times were less tense or somehow easier, and that the most challenging time is the one we’re living in. We often believe we’re experiencing the worst scenarios and the hardest situations, while thinking that others have it easier or that other places are more peaceful. But when you actually go there, you find it’s much the same. In rapidly changing societies, many problems can emerge as a consequence of that progress. With that said, my first Veteran wasn’t so much about individuals but rather about society and the system as a whole. In contrast, the sequel shifts the focus more toward the individual and away from the broader structures of society. For example, there’s a scene where the detective’s wife helps a Vietnamese woman and her children. It’s not done by officials but by an ordinary person. I believe that no matter how hopeless a society may seem, if even one person is fully awake and aware, the seeds of hope are already present. Instead of placing my hope in politicians who make grand statements about saving humanity, I find more hope in everyday people who quietly live their lives, showing care to their family, friends, and colleagues.

Do you notice any changes in the influence of public opinion among the younger generation?

The solidarity of the Korean population is something deeply ingrained in our society, partly due to Korea’s unique geographical situation. Unlike in Europe, where countries are easily accessible by road, Korea feels somewhat isolated from the rest of the world. To travel abroad, Koreans must go by air or sea; there’s no option to simply drive across a border. This, coupled with the division between North and South Korea, creates a sense of insularity, almost like living on an island. Over time, this has fostered a strong sense of solidarity in the country as we’ve had to stick together. However, the younger generation experiences things differently. Compared to their grandparents, they are far more connected to the rest of the world, thanks to the internet and social media. They can communicate quickly and easily with people outside of Korea, which makes them more globally aware. As a result, the notion of community, which was so strong in previous generations, seems to be shifting. While there’s still a strong sense of unity, it’s evolving as younger Koreans engage more with the global community.

Any chance of a Veteran 3?

I’m currently working on an espionage action movie that will depict North and South Korean secret agents clashing as they uncover crimes occurring near the Russian border. As for a third installment of Veteran, I’m actually discussing it with my actors. Depending on the audience’s response to Veteran 2, we might explore continuing the story.

Set in the 1970s, Smugglers (2023) brings to life the riveting tale of female divers caught up in the dangerous world of smuggling. The film earned widespread acclaim for its captivating storytelling, outstanding performances, and meticulously crafted period details.© Next Entertainment World (NEW)